Este es un proyecto colectivo de artistas mayas de Guatemala y mayas/zoques de Chiapas, México. Sin desconocer diferencias de fondo entre la historia y cultura nacional de uno y otro país, en este proyecto se pone entre comillas su “frontera” política actual, y se celebra un territorio cultural pan-maya de una historia milenaria, visto desde el pasado y hacia el futuro.

Es un futuro indudablemente marcado por el presente, por la pandemia ahora y sus consecuencias a mediano plazo. Esta exposición de seis proyectos (cinco individuales y un dúo) con proyectos multimedia, de fotografía, video, pintura y performance, revela de mil maneras como los pueblos mayas e indígenas miran el qué, por qué y cómo responder a la crisis del covid-19. Así redescubren y reafirman su territorio físico y cultural, su autónoma, la fundación de su alma en la relación con la naturaleza, el poder de los pueblos mayas de traspasar fronteras a través de su arte, y la necesidad de atravesar fronteras colonizadoras con diálogos interculturales, como es la asignatura apremiante en este momento en esta parte compleja del mundo.

Sin embargo, la historia hace la realidad, y la frontera (impuesta) es real, ¡y hoy hasta rematerializada como resultado de las políticas nacionales contra la propagación del coronavirus! Finalmente, una dialéctica entre nacionalismo-regionalismo está ampliamente reflejada en este proyecto.

La consideración es de vida-y-muerte y por ello decimos que esta exposición demuestra una nueva biocultura. Todos lxs creadores responden a: ¿Cómo viven la pandemia y las políticas referentes a ella? Personas que vuelven a sus comunidades, personas que no pueden volver. Nos lleva a reflexiones profundas que van de lo espiritual personal y comunitario, a la resistencia crítica al descubrir la hermandad cultural maya e humana tras-fronteras de país, cultura y geografía.

Proyecto Maya Transfronteriza es el producto de múltiples conversaciones iniciadas desde hace dos años entre artistas y con dos curadores, al explorar como el arte contemporaneo maya rompe fronteras, libera creatividad y solidaridad. Va a la pregunta de cómo creadores mayas van redefiniendo su quehacer artístico en la época de pandemia. Es un arte de práctica social, a compartir en las comunidades indígenas de la zona pan maya y en la sociedad en general.

Gracias al apoyo del Centro Cultural de España en Guatemala, y a Raquel Jiménez y Javier Payeras, tenemos el gran agrado de presentar esta exposición en Guatemala.

Lo/as artistas son:

de Guatemala

Marilyn Boror Bor (K’akch’ikel, 1984)

Manuel Chavajay (Tz’utujil, 1982)

Ángel Poyón (K’akch’ikel, 1976)

de Chiapas

PH Joel (Tseltal, 1992)

Saúl Kak (Zoque, 1985)

Säsäk Nichim y Abraham Gómez (Tsotsil, 1980 y 1977)

Los organizadores son del equipo de la Galería MUY:

Martha Alejandro (Zoque, 1988)

Josué Gómez (Tsotsil, 1986)

Artworks

Marilyn Boror Bor

We all want to go to the mountains

Instalation

2020

“Xul es silbato en Kaqchikel, un silbato de barro que suena como un pájaro agudo, este forma parte de una serie titulada “Diccionario de objetos olvidados”, una serie que elaboré cuando migré a la ciudad de Guatemala; estar lejos de mi pueblo significó abandonar hábitos, objetos, pensamientos, cosmovisiones; con este diccionario mis objetos de barro, madera, caña, piedras, etcétera, se inmortalizan y resisten al olvido”.

“Este proyecto surge en medio de una pandemia, donde el encierro y aislamiento se han vuelto la constante, la exploración de la madre tierra se ha cerrado, por lo que la necesidad de estar con la naturaleza se ha vuelto latente y un anhelo.

La ciudad para mí es un paraíso artificial que asfixia con esmog, concreto gris, sonidos de patrullas y ambulancias que debaten con la naturaleza muerta bajo las grandes construcciones.

Esta es una composición del encierro en una ciudad de cemento”.

Marilyn Boror Bor

Fire

Digital photography and video

2020

“Extrañé a mi familia rodeando el calor del fuego, el pollo dentro de la cocina y puse ofrendas de Cuilco blanco, ocote y repensé la lectura del fuego; estaba olvidando lo hermoso de poner semillas de marañón en el centro del fuego para comerlos cuando el fuego se apagará, había olvidado la forma de las tazas que se derriten alrededor del fuego”.

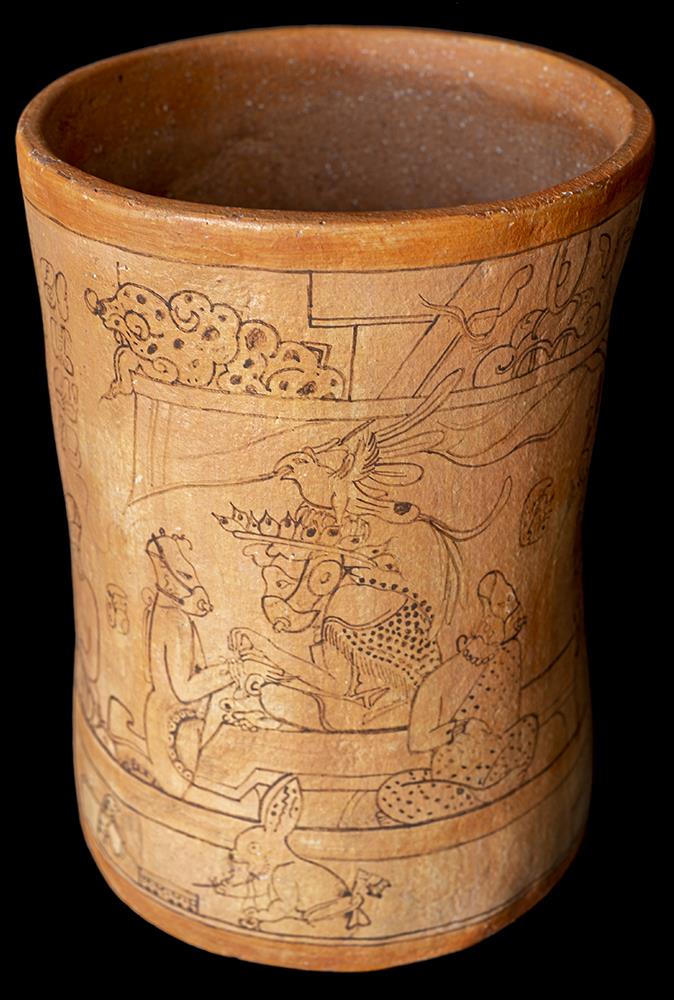

PH Joel

Fotography: Sigh in the face of uncertainty

Sculpture: Classic update

Video: Classic update

2020

“Este proyecto contiene una obra de fotografía, un video y una pieza de cerámica fotografiada (para esta exposición virtual). El video es una recreación de una excavación arqueológica y ¡el descubrimiento de la pieza cerámica (aquí fotografiada)! Vale mencionar que la taza de barro es una reproducción, con modificaciones sutiles, de una famosa encontrada en el Petén, Guatemala (y ahora en el museo de Princeton, EEUU). Finalmente, la fotografía de la pareja en una milpa se sitúa en Chiapas en un asentamiento maya de la Selva Lacandona (dónde el artista y otros han recuperado piezas del período clásico maya).

Esta foto retrata a su padre-madre del artista en tiempos de Covid, cuando el mandado principal se está confirmando: regresa a la tierra, a los orígenes, a la tradición cultural“.

“Cada catástrofe que sucede, ya sean huracanes, sismos o en el caso presente de la pandemia, siempre se responden con nuestros rituales y la medicina tradicional que nuestras madres y abuelas conocen. La fotografía fue un apunte visual de mi reflexión sobre este momento que atravesamos. En ella retrato a mis padres con elementos que frecuentemente se usan para realizar curaciones a diferentes males que en la aldea se presentan”.

“A pesar de la distancia temporal que existe entre la fotografía y la taza policromada estilo códice, ambas comparten la esencia de nuestra cosmovisión como pueblos indígenas, es decir, los rituales”.

“En la superficie de la tasa se observan dos personajes enmascaradas que preparan el sacrificio de un ser humano hacia un Dios del Inframundo.

La desconfianza a los gobiernos y las instituciones que la componen que es producto de nuestra memoria histórica, nos impide ir a los hospitales prefiriendo nuestros propios métodos curativos, a sabiendas de que nuestro destino está en manos de Dios”.

Manuel Chavajay

Wa´aal (Famine)

Sculpture

2020

“Son los espíritus de nuestros antepasados los que nos acompañan el día primero de noviembre. Le ponemos la comida, le damos miel, extendemos nuestra mano y oramos diciéndoles a nuestros ancestros: Ya estás debajo de la cruz; que descanse tu espíritu y que nos visiten en estos momentos; reciban lo poco que tenemos. Terminamos: Nos vemos hasta el otro año; sé el intermediario de nosotros; te estaremos esperando el próximo año”.

Ja qatee ya' nii siilanii

Video

2020

“Es una olla de Amatenango, Chiapas, sobre la cual Chavajay ha escrito la palabra en tz’utujil “Wa’aal”, cuyo significado es aproximadamente la hambruna. Chavajay, durante una residencia en Chiapas en 2018, se interesó mucho por la cerámica como objeto utilitario y artístico maya que se encuentra de los dos lados de la frontera, mismo que se ha convertido en objeto simbólico de su contrario: en lugar de llenar el recipiente con bebida, se encuentra vacío con la palabra significando escasez. Los cántaros – hechos de plástico en Guatemala – son de frecuente comercialización en el sur de Chiapas. Esa ruta comercial se cerró con la coronavirus”.

Saúl Kak

Recipe to survive in times of crisis

Video

2020

“Desafortunadamente estando en la ciudad de San Cristóbal de Las Casas, nos tomó por sorpresa la contingencia sanitaria “Covid-19″, un bicho altamente peligroso. El sistema económico en el que vivimos nos ha hecho depender de productos que vienen de fuera, sin conocer los procesos de preparación, ingredientes, etc. Desafortunadamente muchos de nosotros que venimos de las comunidades hemos adoptado esta forma de vida, dejando a un lado la sabiduría de nuestros padres, olvidando nuestra medicina y alimentación”.

"Survival"

Collage

2020

“Hay dos formas de vida: 1) La que nos ha impuesto, que viene de afuera y es como de conquista. Y 2) la del campo, con la que crecimos, que nos enseñaron nuestros padres, nuestros abuelos. El alimento cultivado por nosotros, en el segundo sistema, es a la vez una especie de medicina, porque te da salud. En esta pandemia, en este tiempo de crisis, la gente del campo va a seguir viviendo”.

"The bomb"

Acrylic on canvas

2020

“Vemos usar las bombas en los campos de cultivos para fumigar a las plagas. Pero somos testigos que se está afectando al campo ya que las plantas dependen de ellas. Si no se les aplican herbicidas, fertilizantes o químicos similares la producción es poca o nula”.

“La imagen de la bomba me representa auto contaminación, pero ver esto en otra condición me re-formula mi idea sobre el uso de la bomba. En este caso se está ocupando para defenderse del virus del Covid-19 que asecha a los pueblos del mundo”.

“En esta pintura, represento al campesino defendiendo a la vida de las pandemias, no solo del Covid-19 sino también de las pandemias extractivas. Se observa en el símbolo del Covid-19, el orden mundial con sus intenciones de despojo nuevamente a nuestro territorio con el discurso del desarrollo y la modernidad”.

Ángel Poyón

Smudge the words

2020

“Anda, escóndete en el temascal, decían nuestras abuelas y abuelos cuando veían alguna amenaza. Desde aquella corrección con el chicote, hasta de cualquier acto civilizatorio (vacunas del centro de salud, los maestr@s buscando niñas y niños para llevarlos a las escuelas), que por ahí aparecían y en el que terminábamos tiznándonos nuestras caras para resguardarnos”.

Säsäk Nichim-Abraham Gómez

Yaxal ch’ulel-kuxlejal

Yikleb kuxlejal

Svunal poxiletik

Spoxil kuxlejal

Photography

2020

“En tiempos de pandemia, la memoria del pasado de los tsotsiles se trae al presente, anuncia un nuevo amanecer y otra resistencia. Curar el alma, sanar el cuerpo con plantas medicinales, ha sido una práctica constante entre los mayas. En lenguaje tsotsil yaxal es vida, naturaleza, agua, riqueza alimentaria, salud. Ch’ulel es el alma y la esencia del ser. Kuxlejal es la vida en su totalidad, persona-naturaleza-microorganismo. El conocimiento sobre el verdor de las plantas es la camisa de fuerza para sanar el alma y curar el cuerpo en el pueblo maya de los altos de Chiapas.

La ciencia occidental sucumbe en el miedo por no tener la cura para el coronavirus, para nosotros se encuentran las plantas y el temazcal. Yaxal poxil se convierte en el sostenedor de nuestra vida, nuestra alma y fortalecimiento para nuestro corazón. Yaxal ch’ulel-kuxlejal es el cubrebocas del miedo y la resistencia contra la muerte. Una muerte anunciada y resistida desde la conquista. Sobrevivimos al pasado, seguimos aquí- ahora, seguiremos con el conocimiento curativo de las plantas medicinales sostenido en la memoria para nuestra permanencia en el futuro”.

Artists

Marilyn Boror Bor

(San Juan Sacatepequez, 1984)

Marilyn Boror es artista visual Kakchiquel, residente en la Ciudad de Guatemala, reconocida por su audáz práctica social comprometida. Graduada en arte por la Universidad de San Carlos, su reporterio abarca la fotografía, instalación, pintura, grabado y performance. Seleccionada para participar en la XIX y XX Bienal e invitada de la XXII Bienal de Arte Paíz 2021, y en la Bienal de Pueblos en Resistencia, Guatemala, Marilyn Boror ha sido incluido en la colección latinoamericana del Museo Reina Sofía de Madrid, España y del Ministerio de la Cultura de Madrid, España.Su trabajo ha sido presentado en diversos espacios expositivos en Alemania, España, México, Estados Unidos, Canadá, Venezuela, Chile y toda Centro América. Su hermana Delcy Boror, también artista, colabora con Marilyn en la composición Todos queremos ir a la montaña.

Facebook: Marilyn Boror Bor Instagram: @marilynboror marilynboror@gmail.com

Performance de “Xul” de Marilyn Boror Bor Este performance parte de “xul”: [šul] la. Flauta. Ocarina. Chirimía. Pito. ¡Hay que liberar a XUL! Varias ocarinas de barro elaboradas por artesanos de Guatemala son liberadas en bicicletas en diversas zonas de la ciudad de Guatemala en tiempo de cuarentena, donde luego de 5 meses seguimos encerrados, ¡XUL es liberado! Se realizará una reunión Zoom, en donde todos los XUL se comuniquen entre sí cuando sean RUXUL (“ruxul” es la forma poseída de “xul”).

Manuel Chavajay

(San Pedro La Laguna, Sololá; 1982)

Hablante de Tz’utujil, habitante permanente de su pueblo de origen San Pedro La Laguna, Manuel Chavajay es uno de los artistas guatemaltecos más reconocidos en su país y en el mundo. Es egresado de la Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas, Rafael Rodríguez Padilla y realizó estudios de historia de arte en el Institute for Training and Development, Amherst, EEUU. Con numerosas exposiciones colectivas e individuales en Guatemala, México, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Estados Unidos, Escocia, Nicaragua, Brasil, Republica Checa, China, Canadá, incluyendo una exposición individual en el Museo de Arte Moderno (Guatemala) en 2018. Manuel Chavajay es promotor del arte contemporáneo en los pueblos mayas. Como artista multidisciplinario en pintura, dibujo, escultura, video e instalación, aborda una crítica decolonial y una reivindicación de la cultura indígena con una mezcla de ironía y profundo y orgulloso apego a su identidad maya.

Facebook: Manuel Chavajay Moralez Instagram: manuelchavajay

Ángel Poyón

(San Juan Comalapa, Guatemala; 1976)

Con múltiples premios y reconocimiento inter- y nacionalmente, Ángel Poyón se aferra a su vida del pueblo natal de habla y cultura Kakchiqel. Sus obras, en los medios de instalaciones, pintura, performance se caracterizan por emplear un idioma del arte conceptual “à la maya”. Como escribe Luis Camnitzer, “Recoge elementos formales pero los pone al servicio de los problemas que su pueblo enfrenta”. Poyón se ha exhibido individualmente, en dúo con su hermano Fernando, y en colectivo, en Guatemala, Costa Rica, República Dominicana, Alemania y México.

Facebook: Angel Poyon Instagram: angelpoyon

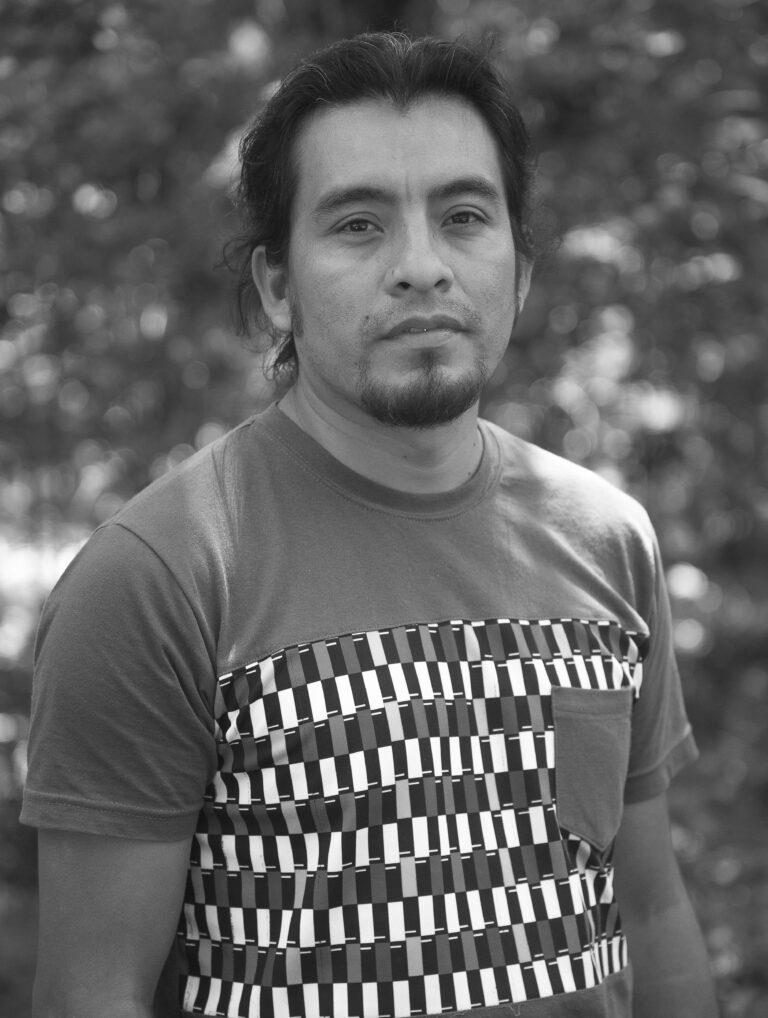

PH Joel

(Ocosingo, Chiapas; 1992)

PH Joel (de origen Ch’ol y Tsotsil) creció en un entorno multicultural a nivel local en la comunidad de Francisco Villa, municipio Ocosingo, compuesta de familias de múltiples grupos lingüísticos mayas, anteriormente acasillados en fincas y ahora autónomos campesinos. Joel (Pérez Hernández) graduó con honores en antropología en la UNACH, en San Cristóbal de Las Casas, y su práctica artística parte de investigación exhaustiva de la tradición de los mayas clásicos de Chiapas y Guatemala, e invención ingeniosa de piezas faux-arqueológicas contemporanizadas. Combina su audacia intelectual con una facilidad autodidacta manual-material. Regresó a vivir en su comunidad de origen desde la cuarentena pandémica de 2020.

Facebook: PH Joel Instagram: pjoelh

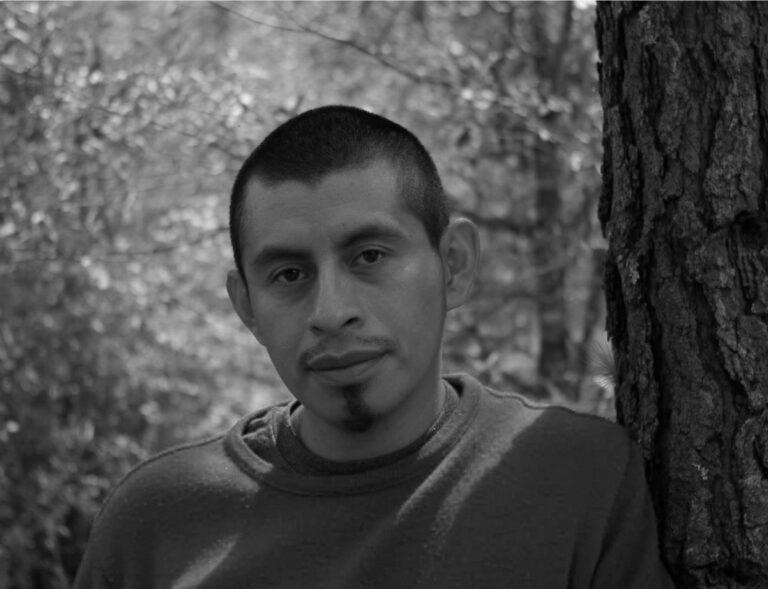

Saúl Kak

(Esquipulas Guayabal, Rayón; 1985)

Heredero de la cultura milenaria zoque-olmeca y hablante del zoque, Saúl Kak es artista igualmente apasionado por la pintura, performance y el video. Consciente siempre de su estatus como refugiado ya que su familia perdió su casa en la erupción del volcán Chichonal en 1982, Saúl sigue muy comprometido con la comunidad que se reconstruyó como Nuevo Esquipulas Guayabal, Chiapas, y ahora su arte está permeado por la difícil defensa del territorio zoque frente megaproyectos, desde represas hasta minas. Kak es Licenciado en Artes Visuales de la UNICACH. Ha sido becado de FONCA. Es, con corealizador Charles Fairbanks, apremiado por largometrajes La Selva Negra y Ecos del Volcán, incluyendo por Mejor Documental en Présence Autochtone: festival de los pueblos originarios en Montreal (2019).

Facebook: Saul Kak Instagram: SaulKak

Säsäk Nichim

(Adolfo López Mateos, Huixtán; 1980)

Nativa hablante del tsotsil, bordadora y asesora de tejedoras organizadas, doctorada en lingüística y profesora-investigadora de la Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas (UNICACH), Säsäk Nichim (Margarita Martínez) se involucró con la fotografía desde hace más de seis años, como codirectora de Club Balam (proyecto internacional de Lower Eastside Girls’ Club, de fotografía con jóvenes de comunidades mayas de Chiapas y de Nueva York). Más recientemente ha llevado su vocación de fotógrafa a su práctica multidisciplinaria de artista pos-etnográfica. Es decir, crea un territorio donde cruce el arte y la antropología, que enriquece (y a veces enfurece) a los dos campos. Säsäk Nichim está activa en espacios de análisis y reflexión de temas de la cultura, lengua y sociedad indígenas e interculturales.

Facebook: Säsäk Nichim Martinez Instagram: sasaknichim

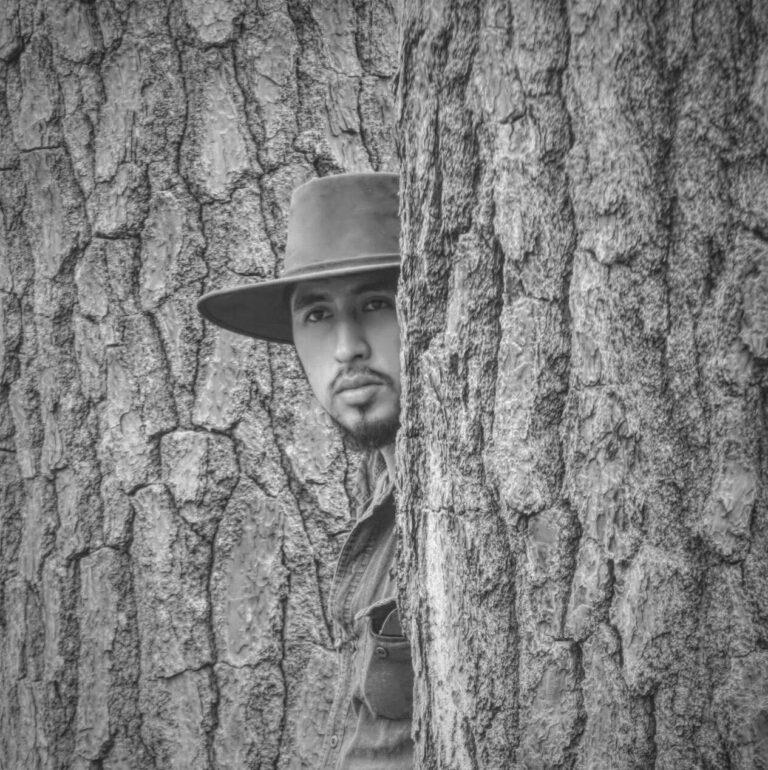

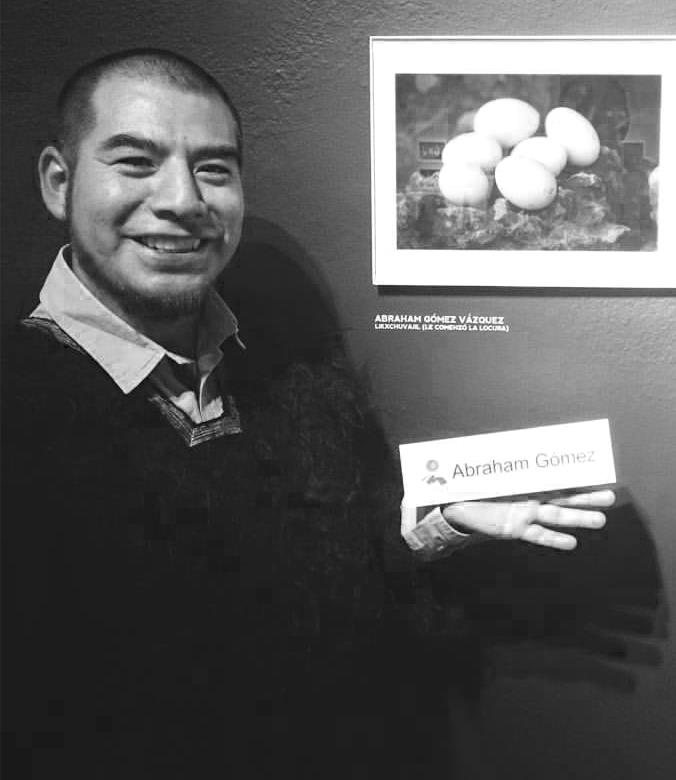

Abraham Gómez

(San Juan Chamula, Chiapas; 1977)

Gómez nació y es comunero en el paraje de Ichinton, municipio de Chamula, Chiapas; combina su práctica artística con su actividad comercial en San Cristóbal. Comenzando en 2012, estudió en el Gimnasio del Arte Chiapas y en 2018 en el Seminario de Fotografía Contemporánea del Centro de la Imagen, Centro de Arte San Agustín, Oaxaca. Fue identificado como uno de los fotógrafos jóvenes más prometedores de México al ser publicado en Develar y Revelar (2015).Entre sus exposiciones fotográficas colectivas están: Chiapaneco –Contemporary Indigenous Photography and Film from Chiapas, en Galerie der Kunststiftung Poll, Berlín, Alemania; y Entre Thanatos e Hypnos en San Cristóbal de Las Casas.

Facebook: abrham Gomez Instagram: abrhamgomez