La Galería MUY presenta obras de Maruch Méndez, con gran gusto y orgullo, como una oportunidad de apreciar su trabajo muy prolífico en los últimos dos años y de descubrir la importancia de su práctica para lxs demás artistas de la MUY.

Habiéndose metido desde los años 80s en el arte de reflexión estética con poesía cantada como performance, tomó un giro al incorporarse en el proyecto de la GaleMUY desde 2015 en los medios de escultura, instalación y la pintura. Vemos una gran libertad tomada por esta artista intuitiva (es decir no de escuela), al haber logrado definir un estilo totalmente propio, con una propuesta artística única: narra eventos de su conocimiento con una interpretación ética expresada en términos animistas. Cuadros que explica siempre terminando con una gran risa significativa y sabia. Un significado pensamos: que ella es propiamente su propia obra. Ella puede ser también el medio por el cual los poderes y la sabiduría de su pueblo se expresan.

Más de un/a artistas maya o zoque ha compartido que la obra de Maruch es influyente con ellos o ellas mismas. Méndez ha provocado gran interés por parte de artistas de ascendencia maya/zoque. Esto se explora en la presente exposición.

P.T’ul por ejemplo identificó la cercanía de Maruch con su material como fundamental en su propio inicio como escultor en cerámica. Antún Kojtom ha admirado la composición en forma de narrativa visual clásica. Saúl Kak reconoce una vitalidad en el estilo esquimatizado que encuentra eco con su propio proceso de pintura expresiva. PH Joel ve una especia de arqueología natural que refleja su propia práctica de rescate-reapropriación de lo clásico. Varios cineastas y poetas (Humberto 13, Xun Betán) están intrigados con la estética verbal de Méndez. Margarita (con Diana Rus) – como íntimas colegas de la artista – valoran el archivo vivo de información en peligro de extinción referente a la figura de los pájaros y mucho más. Cecy Gómez valora la técnica que Maruch emplea en su arte textil. Dyg’nojoch la busca para hacer murales. Al fondo es la autenticidad espiritual con la artística lo que lxs artistas identifican y con el cual se identifican.

Mostramos obras de Maruch Méndez en la MUY con la invitación de que artístas pudieran inspirarse a hacer comentarios y sus propias obras para dialogar con las originales de la maestra. Haremos una recopilación de estas piezas en diálogo, para ir construyendo una exposición compleja en honor de Maruch.

J Burstein W

abril 2021

Artworks

Tu’ch’ich mut (Bird)

Acrílico sobre tela

60 x 50 cm

2018

“Hay un niño le gusta mucho pájaro tuch’ich’, cuando escucha algún canto de este pájaro, el niño lo busca, y cuando lo encuentra le corta el nido después de cortar lo avienta desde lo alto de donde estaba colgado el nido, cuando son huevos de pájaro todavía ahí se quiebra y no los aprovecha, pero cuando ya son pajaritos se los come, el nido no lo tira sino que los cuelga en su casa para jugar, cuando encuentra los pajaritos ya más grandes no los mata si no que nos cría. Eso es lo que hace el niño, pero una vez al momento de ir a buscar el nido y subir en el árbol, desafortunadamente se cayó porque el árbol ya estaba seco, y se lastimó un ojo, porque al momento de caer se le inserto una astilla en el ojo perdiendo un ojo, así que los padres ya aconsejaban no ir a buscar los pájaros y mucho menos subir a los árboles”.

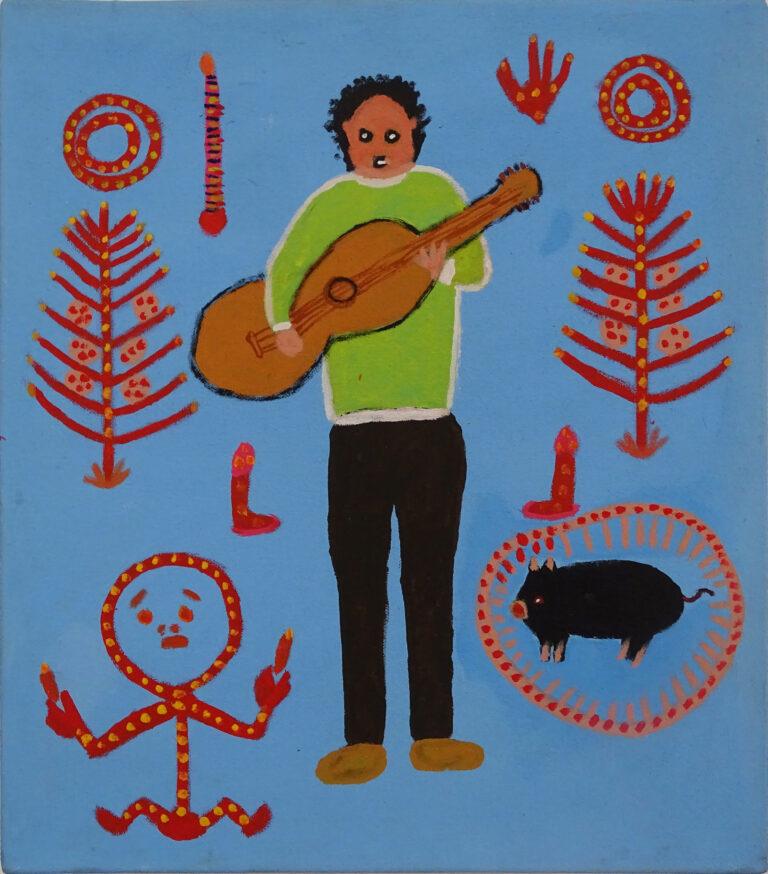

Jchabajon chon (Labrador snake)

Acrílico sobre tela

60 x 50 cm

2018

“Los que sembramos nuestra milpa de lejos no cerca de la casa, así una vez mandaron a un niño a limpiar la milpa, pero el niño regresó corriendo y llorando porque encontró una culebra abajo de la milpa, así que le dijo a su hermana que fueran a ver, ya cuando llegaron vieron que la culebra estaba muerto, ya que el niño lo había matado antes de salir corriendo, así que la muchacha se puso a llorar por lo que había matado a la culebra, pero por esos llantos revivió, ya en la noche cuando se durmió la muchacha, soñó que le estaban agradeciendo por lo que lo habían revivido y diciendo la culebra que él no hacía daño sino que él también apoya en los trabajo de la limpia. Hasta esta fecha ya no matamos a esa culebra y lo dejamos ahí tranquilo, no le podemos hacer daño, tiene la espalda negra y la panza roja. Si ves eso en tu terreno es de buena suerte, ya que tu milpa crecerá muy bien y sin que se eche a perder”.

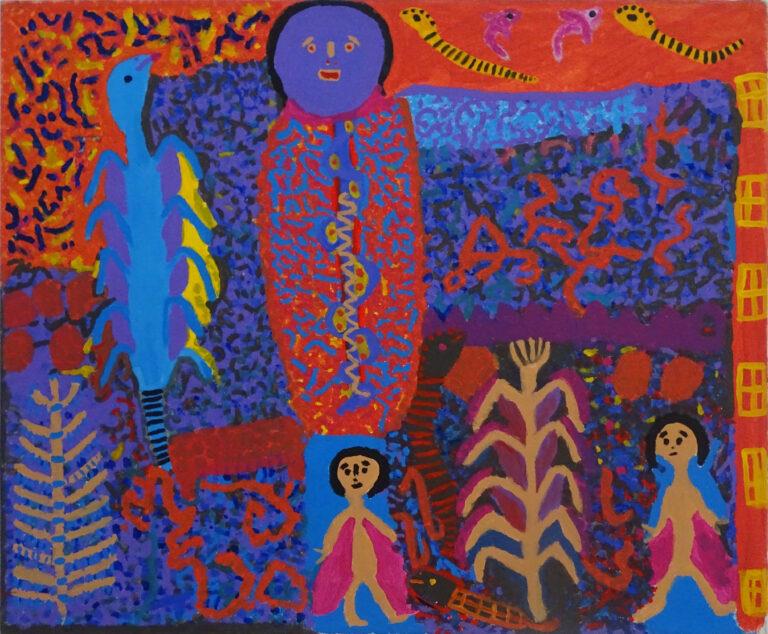

Jsut’ub ik (Whirlwind)

Acrílico sobre tela

60 x 70 cm

2018

“Este es un lugar llamado Xila Ton, donde nació un torbellino, como si fuera una gran culebra, ahí había cerca una casa en donde paso a traer toda la ropa, entonces la mujer que vivía ahí empezó a gritar, entonces de ahí la muchacha vio a un zopilote en el cual le pidió de favor que le devolviera su ropa pero no le hicieron caso, luego apareció una escarabajo lo mismo dijo la chava al escarabajo que le devolvieran su ropa, así que el escarabajo hizo eso y el torbellino regreso en el lugar donde había salido y así toda la ropa regreso en la casa de la muchacha. En el lugar ya habían muchas mujeres porque lo que vieron no era normal, así que buscaron a un curandero para que no hiciera daño, lo ahumaron con miel e incienso le guardaron la ropa por tres días, y le dijeron que igual la muchacha se quedara ahí, porque decía el curandero que podía ser mal presagio, pero la muchacha soñó que no era algo malo si no que era de buena suerte, y que le iban a dar un trabajo se convertiría en curandera, y ella ahora cura rápidamente las enfermedades, también puede curar a las ovejas y caballos cuando se enferman. Y la muchacha le pagan muy bien al curar ya sea a las personas o a las ovejas y caballos. Las medicinas que utiliza son vankilal (Moy), cal y ajo”.

Cemetery

Acrílico sobre tela

50 x 60 cm

2018

“Son los espíritus de nuestros antepasados los que nos acompañan el día primero de noviembre. Le ponemos la comida, le damos miel, extendemos nuestra mano y oramos diciéndoles a nuestros ancestros: Ya estás debajo de la cruz; que descanse tu espíritu y que nos visiten en estos momentos; reciban lo poco que tenemos. Terminamos: Nos vemos hasta el otro año; sé el intermediario de nosotros; te estaremos esperando el próximo año”.

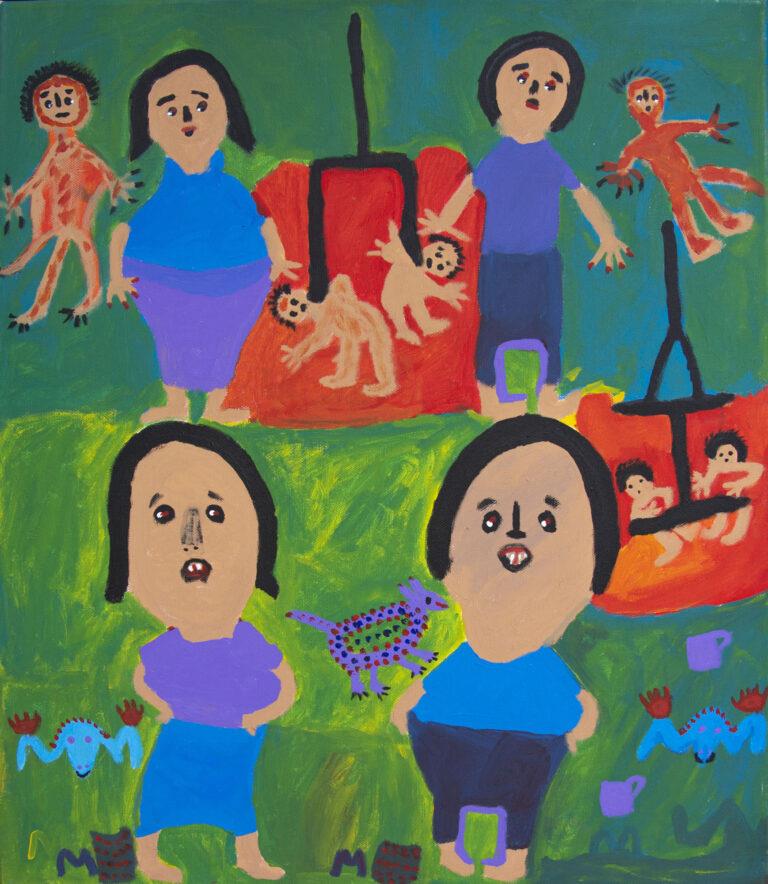

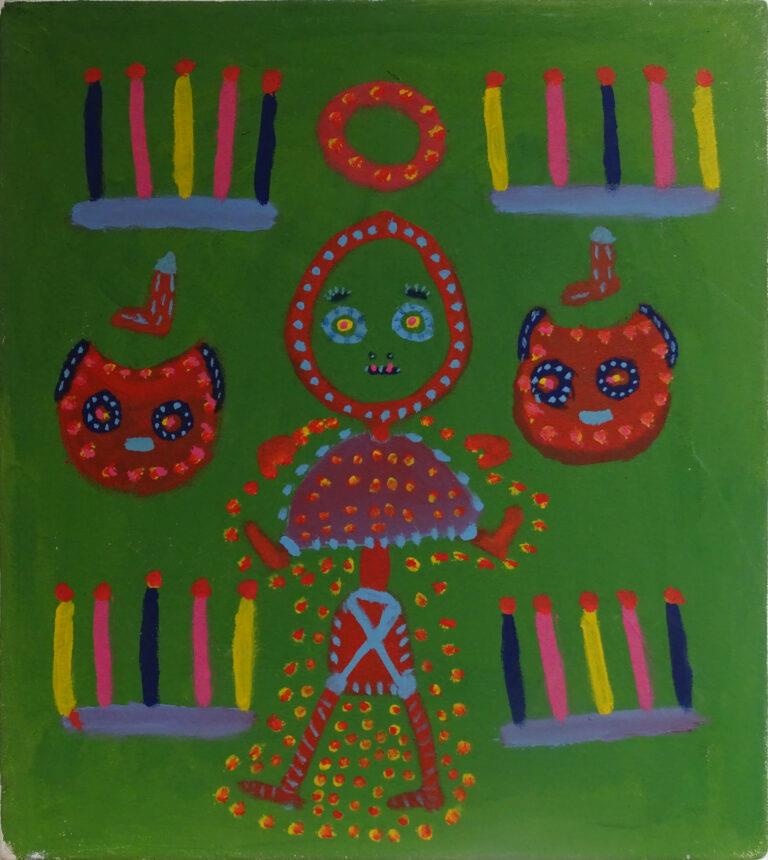

K’atinbak (Hell)

Acrílico sobre tela

60 x 50 cm

2018

“Se trata del inframundo; muestra que hay personas con muchas maldades y otros con menos maldades, y ya están pagando por sus pecados. En la pintura muestra un diablo que antes fue una persona pero muy malvada: se abusaba de sus hermanas e incluso sus hijas. Por esa razón le nació una cola. De hecho esa persona cuando vivía se fue tres días y noches en la cárcel, que ahí no le daban comida. Lo único que le dieron fue tres manojos de rastrojo y tres manojos de zacate, porque le decían que eso merece los que se comportan como animales. Y en el infierno ya no le daban agua. En cambio los que no pecan mucho sí les dan un poco de agua. A las dos personas que se ven en la parte inferior de la pintura les dan agua”.

The devil's work

Acrílico sobre tela

67 x 80 cm

2018

“Las personas de ahora dicen que la vida ya está muy mal: ya tanto mujeres y hombres se ahorcan. Pero realmente el diablo es que influye ahí. Así pasó en mi pueblo: a una muchacha no le dejaron casar con un chavo y se ahorcó. E igual un muchacho que no le dieron permiso de casarse con una muchacha que conoció se ahorcó también. Él que influye ahí es el diablo, porque anda persiguiendo y viéndonos, y trata de hacernos caer y hacer acciones como ese tipo que hicieron los jóvenes”.

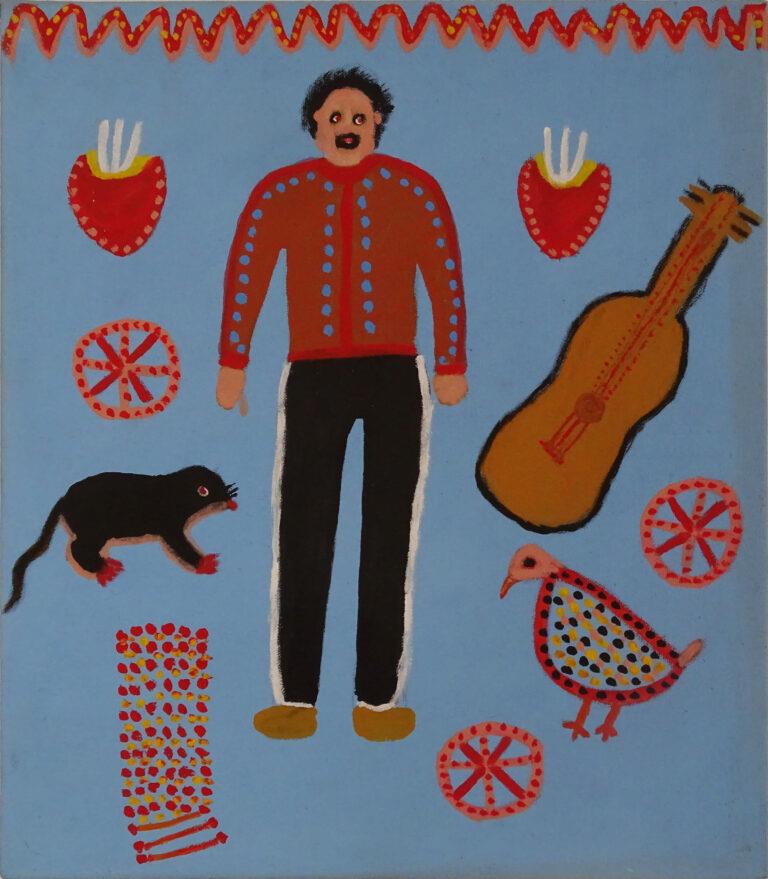

Xch’ulel zorro (Fox spirit)

Acrílico sobre tela

66 x 64 cm

2019

“Este montoncito de niños son estudiantes de la escuela. Del lado izquierdo son tres maestros. Los niños eran muy juguetones, no entendían, no obedecían: estos maestros no les tuvieron paciencias y los pegaban. Tenía una barra y les pegaban en las nalgas y en la cabeza. Y los niños comenzaron a perder el sentido, ya tenían problemas de entendimiento. Luego la mamá se fue a quejar con el agente porque se le había dañado a sus niños. Decidieron correrlos a los maestros, hasta que llegó una maestra y ella les habló, los llevó debajo de los arboles, les daba manzanas, les hablaba con cariño y también le pedía mucho a Dios que ayudara a estos niños, que comprendan, y así mejoraron, a entender. La maestra se dio cuenta que los niños tenían nahuales – un zorro y cuando son zorros, uno es muy juguetón. Sólo se está divirtiéndose. Por eso tenían esa actitud. Así que la maestra les cambió a todos el nahual, y al cambiarles el nahual ellos fueron niños obedientes, mejoraron. Esa maestra duró muchos años trabajando con ellos, casi treinta años y terminó preparando a dos, muy bien a dos”.

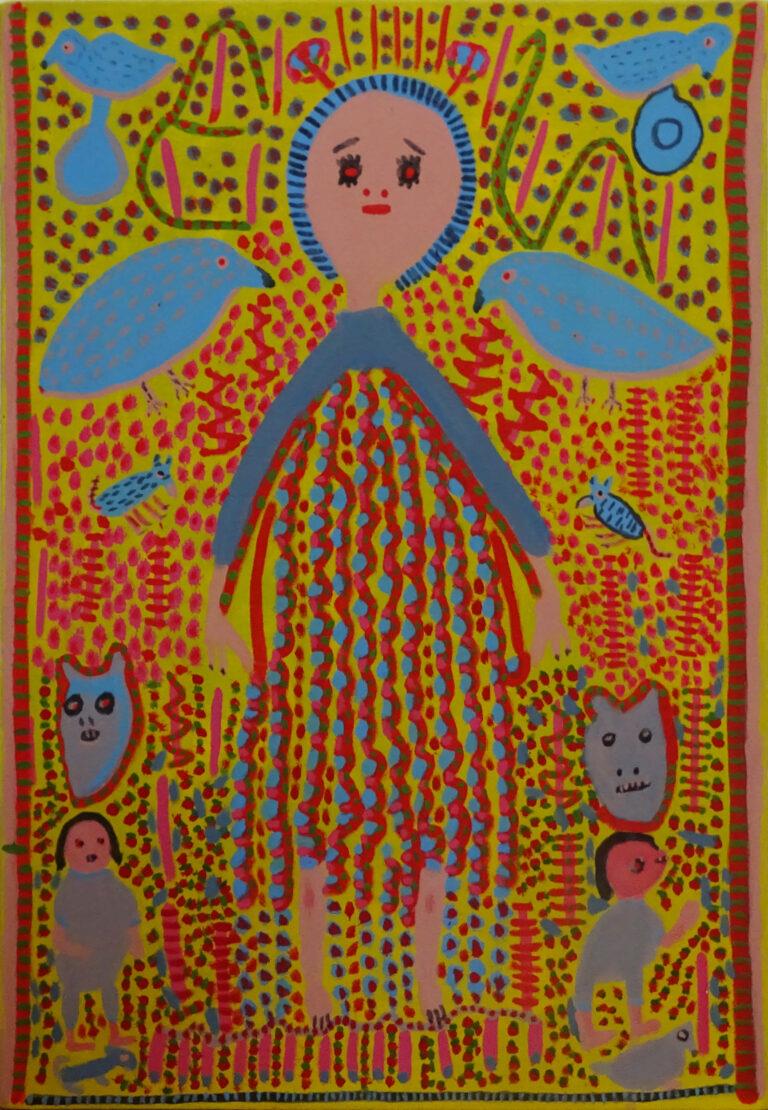

Yajval vo (Owner of water)

Acrílico sobre tela

65 x 45 cm

2020

“Es el señor del agua, es un ángel. Hay unos pájaros al lado, que se llaman k’’l. El Ángel les da indicaciones a los pájaros. Cuando están las nubes oscuras, cuando están cargadas de agua, eso les da indicaciones a los pájaros y ellos comienzan a cantar fuerte. También cuando están las nieblas fuertes, también salen, se despiertan los diablos. Por eso hay que cuidar a los niños pequeños”.

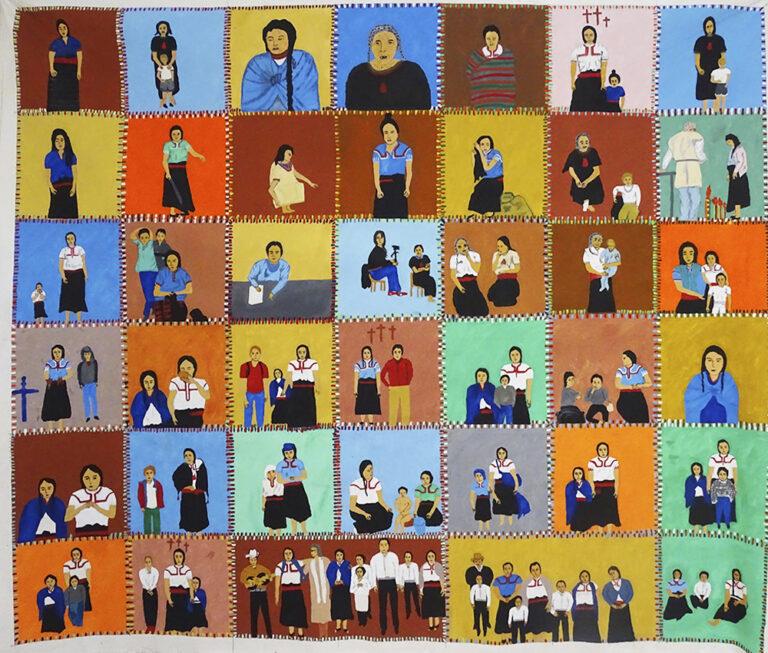

As a mother

Acrílico sobre tela

154 x 180 cm

2020

“En esta obra, pinté como es que crie a seis niños. Cuando me preguntan, les cuento, como es que los tomé como mis hijos, y como tuve que cuidarlos, porque eran muy chiquitos. Cuando el papá de ellos se ahogó cuando estaba tomando pox. Entonces yo les tuve que criar y darles educación, porque la mamá de los niños, no sabía trabajar y no tenía como apoyarlos. Así me tuve que hacer cargo de ellos, fueron creciendo los vi salir de la escuela, antes no había tantos apoyos como ahora. En aquel momento yo me tuve que hacer cargo de los gastos de las graduaciones, hubo fiesta en sus salidas de sexto grado conseguí dinero para eso y para los padrinos, eran muy buenos siempre les recomendé que pusieran atención que no se escaparan de las clases y así salieron bien. Solo estudiaron hasta el sexto grado todos, después de terminar la primaria los bauticé a todos, tuve que avisarles a mis amigos que estaban en San Cristóbal para que fueran padrinos y así fueron bautizados. Los considere mis hijos le pedía adiós que crecieran bien, que no se perdieran un día, a veces lloraba un poco porque quería lo mejor para ellos, porque los quería, aunque yo no tuviera un hijo. A ellos los consideraba mis hijos, y así les di lo que ellos necesitaban, y hasta el día de hoy ellos me siguen tomando en cuenta. Cada año siempre regresan me visitan vuelven a mi casa, nos pasamos juntos en todo santo, ellos eran muy pequeños cuando llegaron, me acuerdo que cuando llegaron pedían chichi (leche) por las noches empezaban a llorar, me levantaba y les daba sus tortillas y algo de comer”.

.

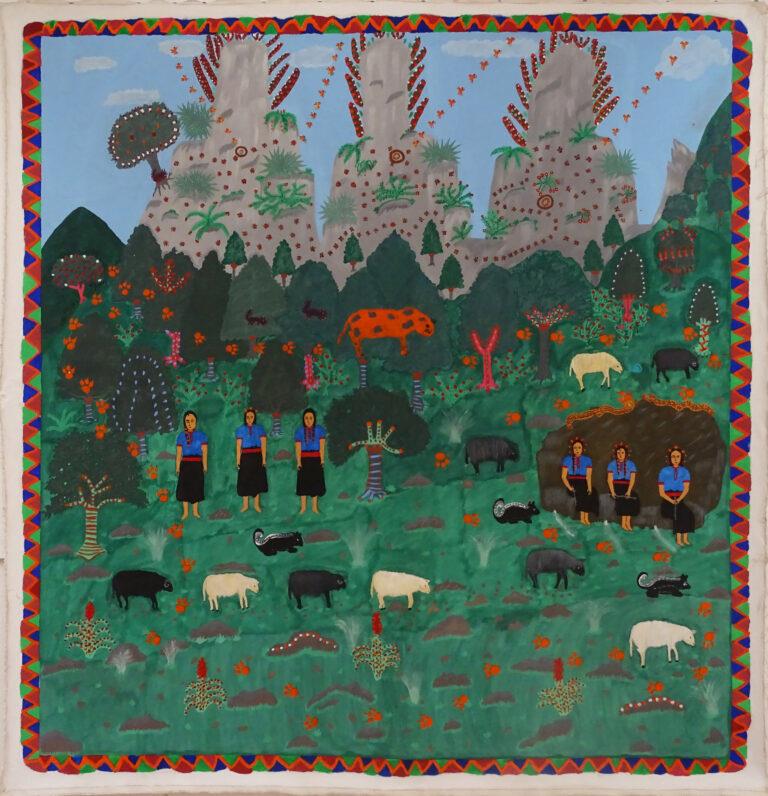

Three women

Acrílico sobre tela

180 x 173 cm

2021

“En esta obra, habla de tres mujeres que vienen de tierra roja arriba de Ixtapa, llegaban a pastorear sus borregos en un lugar donde encontraran buen pasto. Estas tres muchachas se sentaban siempre en una roca ondulada, todo el tiempo se sentaban ahí. Siempre que iban a pastorear sus borregos solo se sentaban en ese lugar, pasaban meses y ellas seguían ahí, pero ellas no sabían que en ese lugar era fuente de agua para los animales como el tigre, el zorro, el tejón, el armadillo y la ardilla. Como ellas llegaban desde muy temprano se iban hasta muy tarde, el tigre solo daba vueltas y vueltas todo el tiempo, tenía ganas de tomar agua, pero no puede porque hay están las muchachas.

Este jaguar como tenía sed, le pidió a las culebras que fuera asustar a las muchachas, ahí en donde estaban sentadas llegaron las culebras, ellas no se asustaron y dijeron que solo vinieron a descansar las culebras sobre las piedras, arriba hay tres arroyos, el dueño del arroyo gritó fuerte: Muchachas algo les va a pasar a las tres, algo va a suceder en sus vidas, ellas no hicieron caso y no tomaron importancia lo que escucharon.

Al siguiente día fueron a pastorear y se sentaron en el mismo lugar, de repente desaparecieron, en un cerrar de ojos ya no estaban se convirtieron en rocas muy gigantes, antes estaban sentadas todo el día, pero ahora sus castigo es, estar paradas todo el tiempo convertidas en rocas grandes, sus padres lloraban y lloraban porque buscaron a sus hijas en todos lados pero nunca las encontraron, las castigaron porque hacían sufrir a los hijos de la naturaleza al taparles el lugar en donde tomaban agua”.

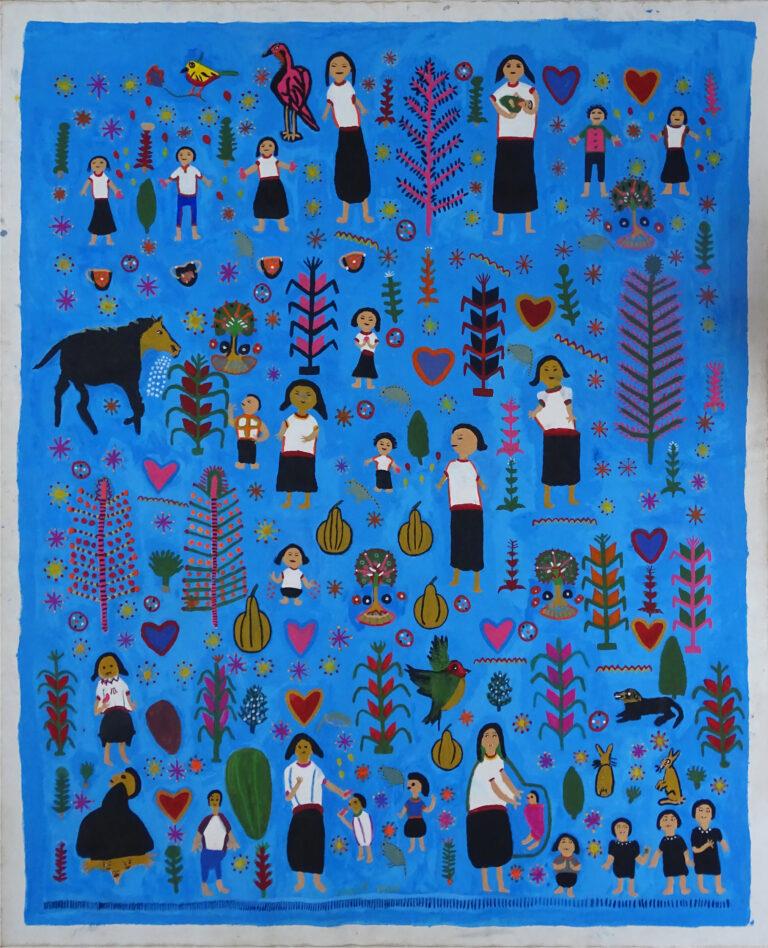

Smoton jk’ajvaltik (Gift from God)

Acrílico sobre tela

180 x 152 cm

2021

“Adopté a seis niños, los adopté muy pequeños de 2, 3, 5 y máximo de 6 años. Cuando los adopté tomé toda la responsabilidad, en darles comida, ropa, y educación. Cuando los niños ya tenían tres años los mandé a la escuela (kínder) y los mandaba ya bien comidos, porque no teníamos dinero, no podía mandar con gasto, por eso ya iban desayunados, yo les cocía verdura y ellos querían chile en sus comidas, se comían entre tres y cuatro tortillas. Cuando regresaban de la escuela, ya tenía preparado sus comidas, calabaza con elote y papa roja (cosecha de mi huerto). Ellos comían muy bien, no sufrían de hambre. Como no tenía dinero no podía comprar carne de res, pollo o puerco para la comida, pero sabía comer ratón de campo y sabía hacer trampas. Íbamos con los niños al monte para capturar los ratones, y esa era la carne que comíamos.

Los niños usaban ropa tradicional nunca se pusieron ropa de la ciudad, eran muy contentos, les gustaba mucho la escuela, siempre sonreían y cantaban de alegoría por la vida”.

“En la obra hay un caballo estaba amarrado cerca de mi milpa, en una ocasión se soltó y se comió toda mi milpa, los niños empezaron a llorar porque ya no tenían elote y maíz”.

“El conejo que está en la obra, era el que se comían toda la verdura que sembrábamos en el huerto. todos los días llegaba a comer, cuando los niños veían el conejo, llamaban al perro para que los cazara. El perro persigue el conejo en el bosque y después de un rato, regresaba el perro con el estómago lleno. También hay un árbol de aj-te’ (árbol de matasano), los niños se la pasaban jugando trepando el árbol, y comiendo la fruta del árbol, poniéndole sal o azúcar y así la pasaban feliz todo el día. Hay un personaje que le dio el espíritu a los niños (el papá de los niños), quien murió ahogado de un sorbo del alcohol, él estaba sentado y mientras estaba tomando una copa de trago se ahogó y después de un rato se murió”.

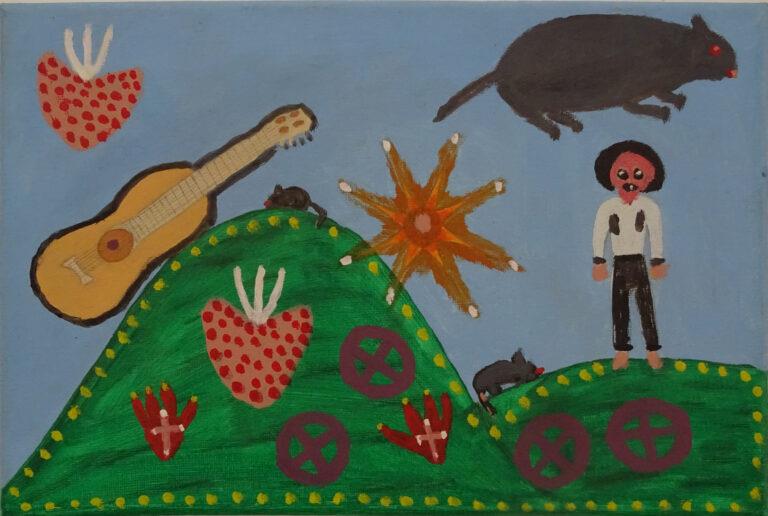

The hills

Acrílico sobre tela

35 x 40 cm

2020

“Estos tres cerros, es lugar donde la gente acude con sus velas, para tener mejor economía, pero como hay este coronavirus, la gente va también a los cerros por sus salud, que estén protegidos físicamente, ni por nada sea permitido la enfermedad a las personas, esto le dicen a los dueños de los cerros”.