Dos artistas fascinados por el volumen, lo táctil, el movimiento: la escultura. P.T’ul remonta en el tiempo a los usos culturales del lum (tierra), contemporizándolos en un gesto de recuperación de la tradición oral maya a través de moldeo manual del barro. Gerardo K’ulej, recoge materiales naturales – y otros a veces locos – para construir objetos emanando las inquietudes/celebraciones existenciales de sus sueños y reflexiones espiritu-intelectuales. Dos artistas: jóvenes comprometidos y consumidos por sus proyectos escultóricos, en los cuales lo material significa y los significados materializan.

Pedro Gómez, o P.T’ul, (Chonombyakilvo’, San Andrés; 1997) es un artista emergente que rápidamente encontró su camino como ceramista tanto de obras escultóricas así como utensilios de alto diseño. Su material preferido es local (de San Ramón, del valle de Jobel). Varia su técnica de quema, a veces en fogón abierto, a veces en horno de alta temperatura. Y como se ven en sus textos acompañantes moldea sus formas basado en su memoria, su investigación con los ancianos y el subconsciente colectivo de su pueblo.

P.T’ul llama “maestro” y “maestra” a quienes le han abierto este camino; todos con el mensaje a él de entrar libremente en su exploración a través de la prueba-y-error conocido por cualquier ceramista en su encuentro directo con el material. Él habla de Maruch Méndez, de Jerónimo Morquecho como sus maestros principales. (Parte del material usado viene en parte de Pablo Millán donado por Willy Millán.)

Gerardo K’ulej (Chilil, Huixtán; 1988) inició en el arte hace cuatro años, con una inquietud muy propia: entender relaciones entre el arte y la ciencia. K’ulej es bioquímico con el grado de maestría, con experiencia en la investigación y la docencia. K’ulej es un pensador abstracto que emplea – tal vez más que las palabras – las representaciones físicas de sus conceptos. Ahí los objetos, que “hablan” por sí mismos. Son profundas reflexiones sobre el espacio y el tiempo. No falta una concretización en ellos: él habla de su fascinación por la ciencia maya, clásica y en procesos de revalidación. Claro, tampoco falta el sentido del humor con un flechazo de sonrisa (único de Gerardo).

De las interlocuciones importantes en su búsqueda muy propio, Gerardo señala a Federico Burkha (escultor), Kees Grootenboer (escultor y arquitecto) y Misgav Har-Peled (intelectual). Mediante sus colaboraciones con Antún Kojtom y Maruch Méndez, K’ulej entra plenamente en el campo del arte maya social y espiritual.

La realización de esta exposición debe enormemente a la interlocución de los artistas con Marta Turok, gran especialista en el arte popular y arte indígena de México y curadora invitada a esta exposición. Juntos exploran un campo complejo del arte mas allá de las categorías de moda: artesanía, arte popular, arte moderno y contemporáneo. No rechazan ni olvidan sus culturas propias; tampoco están encerrados en ellas. Es una arte basado en diálogos.

Artworks

Equilibrium

Gerardo K'ulej

Piedra, madera y metal

2019

“La naturaleza se abre camino y pasa por sí sola, ella misma encuentra su estado natural, crece de manera armoniosa, aunque el hombre le arrebate su corazón, ella sana. Somos el espejo de nuestros actos, la arrogancia y la ambición de obtener valor a partir de la naturaleza, eso nos llevará a nuestra destrucción”.

The breakdown of territory

P. T'ul Gómez

Terracota, lana, hilos y tecomate

2019

“Esta pieza representa a mi pueblo San Andrés Larrainzar que se sigue dividiendo por partidos políticos, creencias religiosas y la economía. El día de hoy ya no se retoman los pensamientos de los ancestros que mantenían un pueblo unido y fortalecido. Las familias se rechazan y ya no se comunican. La cadena y el candado representa el poder que solo algunas personas tienen, buscan dirigir al pueblo como presidentes o lideres de una organización, manejan al pueblo a su conveniencia sin respetar los derechos de las mujeres, niños y hombres. Ya no hay conciencia por la salud, por la educación y la naturaleza. Eso hace que se rompan los valores del pueblo”

Transport change

P. T'ul Gómez

Terracota

2019

“Anteriormente los animales, como el caballo, el burro y el asno, son los que ayudaban al campesino, y formaban parte de su vida. Cargaban leña, costales de maíz y frijol.. Se alimentan de pasto y agua. Y los que tienen un cargo de capitanes hacen un recorrido en caballo alrededor de la iglesia de San Andrés cargando consigo banderas”.

The church offering

P. T'ul Gómez

Terracota y tinte natural

2019

“En la iglesia de San Andrés tenemos muchos santos, cada uno necesita alguien que los cuide, les lave la ropa. Eligen a una persona para hacer todo el trabajo y se llama martoma, y cuando acepta y recibe ese cargo tiene que juntar a sus familiares y es importante que estén los que han tenido ese cargo para recibir los consejos. El martoma ofrece un convivio con la familia y sus invitados. Sacrifica un toro, ofrecen la primera comida. La res es una muestra de unidad y fe, ya que es el punto donde se comparten ideas sobre la tradición. El martoma se viste con su traje tradicional. Un guía le presenta con el santo. El martoma ofrece la fiesta deseando que su cargo pase bien. Las personas invitadas tienen que estar tres días acompañando al martoma en lo que toma su cargo. Es importante ayudar, las mujeres cocinan, los hombres cargan agua y las personas mayores rezan y bailan con la música. Las manchas que tiene el toro representa las energías que se combinan”.

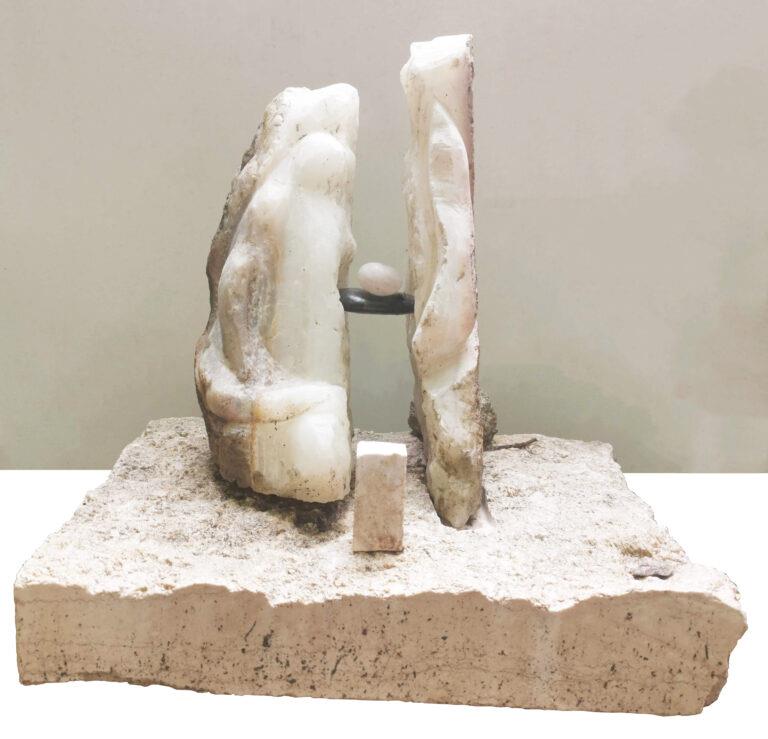

Poles

Gerardo K'ulej

Piedra, metal, madera e imán

2019

“Una columna sosteniendo un efecto físico, fuerzas de atracción por polos diferentes, acaso no es igual que la cultura, somos mundos de diferentes polos y eso nos hace especiales, la diferencia está en nuestra forma de ver e interpretar la vida, en ocasiones necesitamos adicionarle un peso extra, para obtener el equilibrio”.

Cha’bivanej (Carer)

P. T'ul Gómez

Terracota y lana

2018

“En San Andrés Larráinzar cuando se construye una casa, en medio entierran la cabeza de un ganado para ofrendarlo al suelo. Para que él espíritu del animal cuide a los habitantes, protegiéndolos de seres de la oscuridad y demonios que causan enfermedades. La gente del pueblo aun cree en esto para vivir con tranquilidad y confianza en su casa”.

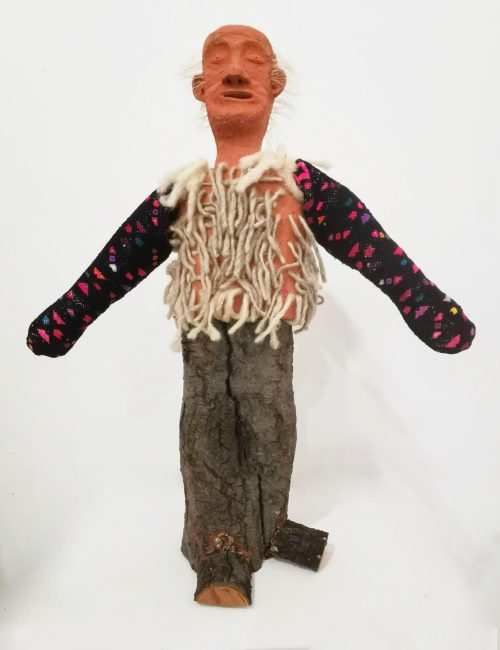

Ik’vanej (He who carries)

P. T'ul Gómez

Terracota

2019

“Hemos escuchado sobre el perro que guía el alma de las personas hacia el inframundo en un camino estrecho y oscuro después de la vida. Cuando el cuerpo llega a su descanso la muerte recoge a las personas, el alma empieza otro viaje. Mi mamá decía que un perro negro carga nuestra alma y nos ayuda a cruzar el océano y la oscuridad. Por eso en esta vida no debemos maltratar a los perros, porque ellos nos guiarán hacia la luz. Si los hemos molestado tirarán al agua nuestro espíritu, pasaremos mas tiempo en la nada sin rumbo y sufriendo. Dependiendo de como fuimos en la vida, de ese color será nuestro guía, tenemos tres opciones puede ser un perro amarillo, blanco o negro. Cuando éramos pequeños, una prima me contó que nuestra alma pasa mas tiempo en la tierra recorriendo todo lo vivido, acariciando lo que alguna vez nos hirió. Nos disculpamos de todo lo que hemos maltratado, también recogemos lo que hemos”.

The emotions

P.T'ul Gómez

Terracota

2019

“Esta pieza representa las emociones que tenemos las personas, en ocasiones gritamos de coraje, felicidad, o a veces estamos tranquilos. Aprendemos a manejar nuestras emociones hacia nuestro favor. Las emociones positivas tenemos que escucharlas y sentirlas, porque nos ayudan a sostener nuestras ideas y hacernos formal con nuestra personalidad y actitud”.

“La parte de arriba de la pieza, representa nuestro cerebro donde guardamos nuestras ideas para generar cosas nuevas y el cuerpo es la personalidad que cada uno tiene”

Jtotik, jme’tik (Our father, our mother)

P. T'ul Gómez

Terracota y tinte natural

2019

“Mis abuelos al sol, le dicen padre, se le debe agradecer todas las mañanas por iluminarnos la vida. A la luna le dicen madre, hay que ser agradecidos con ella por su presencia. En las noches orientan nuestros sueños, nos alumbran y guían nuestras vidas. El sol y la luna sostienen nuestras vidas, nos permiten seguir en la tierra”.

“La luna y el sol, ayudan a crecer nuestra alimentación en la tierra. Nos refugiamos en las mañanas con el sol, en el anochecer entregamos nuestra mirada y nuestras fuerzas cansadas de las actividades del día a la luna. A través de nuestras oraciones le hablamos de nuestros sueños, lo que deseamos en nuestro trabajo. La luna nos sostiene para continuar nuestro camino. Ellos conocen nuestros sentimientos, ven todos los días a la humanidad y les podemos hablar en todo momento”.

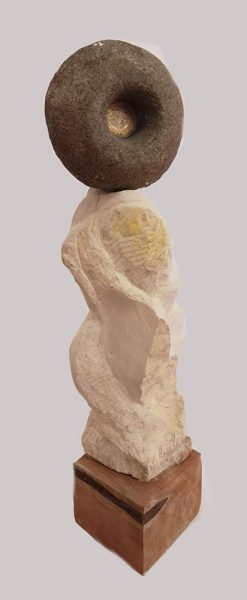

Geometry

Gerardo K'ulej

Metal, piedra y madera

2018

“De lo rectángulo a lo abstracto, una representación de la simplicidad de nuestro mundo, un lenguaje de la imaginación que cambia de una representación del mundo donde vivimos, una piedra anclada a la visión de nuestra tierra y toda la complejidad cósmica donde estamos envueltos”.

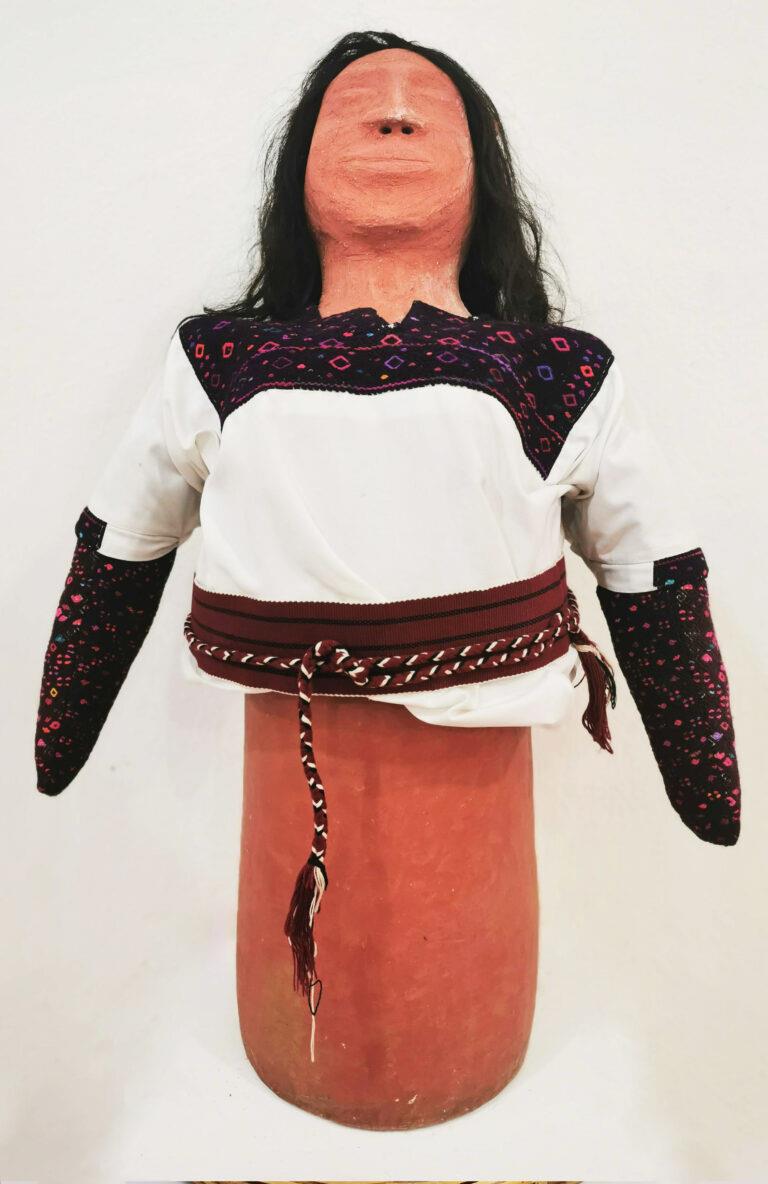

Symbol of consciousness

P. T'ul Gómez

Terracota

2019

“En el pueblo de San Andrés Larráinzar, las mujeres dejan crecer sus cabellos, pasan los años y no lo cortan, el cabello largo representa la belleza. Cuando tienen un cargo se hacen una trenza que se acomoda alrededor de la cabeza, es un símbolo de conocimiento y sabiduría experimentado por los ancestros y muestra de autoridad. Son vistas con respeto y llamadas por el cargo que han ocupado, por tener fortaleza de resistir y contribuir en las responsabilidades que el pueblo necesita”.

Hybridization

Gerardo K'ulej

Madera, piedra y metal

2019

“Somos el resultado biológico de la genética, hibridación de culturas y pensamientos, somos formas y colores desde el arte genético. Lo que eres, es la mezcla de todas las culturas del pasado, es absurdo pensar en diferencias humanas, y de razas. Por ello la palabra clave de los mayas Ixh ala k’en yo soy otro tú y tu eres otro yo“.

The weavers

P. T'ul Gómez

Terracota

2019

“La araña teje su casa con sus hilos, dentro o fuera de las casas de las personas. Ahí nacen sus hijos, no es bueno matarlos cuando están dentro de la casa. Las personas tienen que pronunciar om om om (araña) cuando matan una araña, o si no, perdido, juntamos los cabellos y los pedazos de piel por si alguna vez nos hemos cortado, hasta que juntamos todo. El alma encuentra su descanso y finalmente puede viajar junto con el perro negro, blanco, o el amarillo hacia la luz”.

Yalemvek’et (Skull)

P. T'ul Gómez

Terracota

2018

“Hay personas en el pueblo que se dedican a espantar como un esqueleto a la gente por la noche, pasa caminando en la puerta de las casas con la intención de dejar enfermo a alguien de la familia. Casi al amanecer regresa volando, donde dejo su piel y le habla tres veces muyan vek´et (sube cuerpo) y la piel comienza a acomodarse de nuevo a los huesos. A la siguiente noche esta persona de nuevo deja su piel por el bosque, repite tres veces yalan vek ´et (baja cuerpo). La piel se desprende del esqueleto y se queda amontonado por el suelo, y el esqueleto vuela hacia su victima a molestarlo. Los que encuentran la piel amontonada le ponen ajo, pilco, sal y limón para que la piel no suba a los huesos de la persona y así morirá el que practica esta forma de asustar”.

The meeting of nahuals

P. T'ul Gómez

Terracota, botella de vidrio e hilos

2019

“Cada año los nahuales de diferentes lados tienen un encuentro para dialogar sobre la humanidad y de lo que pasó en el año. Después acuerdan las reglas para el siguiente año. Se van a las ruinas o al bosque, donde se encuentran los nahuales de cada persona y deciden a que alma para ofrecerle un don especial. Le pasan su sabiduría para continuar con el trabajo que la vida les ha dado. Hay nahuales buenos que te curan y piensan cómo proteger a las personas. Y también hay nahuales que te hacen tener experiencias fuertes a través de sueños o pasando por enfermedades que te llevan hasta la muerte. Es un trabajo que les ofreció la naturaleza donde hablan de sus actividades y deciden como manejar el don que tienen”.

A wild town

P.T'ul Gómez

Terracota y tinte natural

2019

“Mis ancestros eran salvajes, cuando tenían que defender al pueblo de San Andrés Sakamch’en de los Pobres manejaban conjuros, tenían ideas sagradas las creencias y ceremonias que les habían inculcado sus padres. Eran tan importantes que lo utilizaban para trabajar y vivir en la tierra, por eso lo transmitían a las nuevas generaciones. El traje de las mujeres y hombres lo tejían con sus manos, hacían sus propias vestimentas era una muestra de libertad para no depender de las fabricas. También tenían comunicación con el espíritu humano y el animal juntos hacían continuar la tradición. Los mestizos molestaban y explotaban a los indígenas cuando llegaban a vender sus productos a los municipios, les robaban y abusaban de las mujeres, a los hombres los golpeaban. Los discriminaban por su lengua tsotsil y sus trajes tradicionales. Eran maltratados y humillados todo el tiempo, un día tuvieron que unirse y demostrar que no iban a soportar las injusticias para siempre, dialogaron por la vida de sus hijos y nietos que iban a crecer. Tenían que ser libres, por eso decidieron correr a los mestizos que dominaban al pueblo. Los indígenas tuvieron que demostrar su espíritu salvaje para liberar sus tierras del sufrimiento, utilizando la razón y manejando la fortaleza que la naturaleza les da a sus hijos”.

Max (Monkey)

P. T'ul Gómez

Terracota

2019

“Mis abuelas y mi madre hablaban sobre un personaje que le decían: Max (Mono), que se dedicaba a cambiar de vientre a los bebes. Llegan en las noches, cuando una mujer embarazada esta dormida, le quita a su bebe y lo lleva a otro vientre, aunque tenga varios meses o esté a punto de nacer. Ya nace con otra madre y su mamá verdadera no sabe porque se ha ido su bebe. A los bebes ya nacidos le hacen un amarre en sus pies y su manos con un hilo de color blanco para mostrar ser parte de la familia. Este personaje es como un dios, que busca una mejor vida para los bebes en donde puedan crecer. A la mujer que le llega el bebe lo recibe como un regalo. Es por eso que en ocasiones los bebes no se parecen a sus padres, ya que la mujer no se da cuenta como ocurrió su embarazo. Hasta el día de hoy este espíritu sigue apareciendo y formando parte de la cosmovisión del pueblo de San Andrés y otros pueblos indígenas”.

Me’xpak’inte’ (Mist woman)

P. T'ul Gómez

Terracota y cabello

2019

“Las personas del pueblo hablan de la Me’xpak’inte’ (Mujer Neblina). Sale en las montañas cuando hay neblina, confunde a los hombres, se hace pasar por una mujer muy hermosa. Cuando un hombre esta borracho la Me’xpak’inte’ se hace pasar por su esposa; inconscientes, los hombres empiezan a ir sin rumbo. Un andar donde la realidad no se percibe, se tiene una imaginación muy hermosa. Un camino lleno de flores con mucha luz. Pero termina todas las maravillas y luego se encuentran rodeados de muchas plantas con espinas, en un terreno oscuro y desconocido, o los lleva en su cueva. En su sueño de sus familiares el borracho les llega a avisar en qué parte se encuentra, para ir a rescatarlo antes que se cumplan los tres días. Y si no, ya no podrán sacarlo. Porque la Mujer Neblina los lleva a otro lugar. Las personas mayores y los que saben sobre la Me’xpak’inte’, dicen que cuando uno sale a buscar leña por las mañanas o en los atardeceres nublados, recomiendan voltearse la camisa y el pantalón o llevar el pilco (una planta sagrada que lo preparan para que no los engañen con la Me’xpak’inte’’ y los espíritus de la montaña)”.

The circle of life

P. T'ul Gómez

Café, pasta de café, barro y telas

2019

“Esta pieza hace referencia cuando nacemos, empezamos a absorber y a construir aprendizajes de nuestros padres y de lo que vemos alrededor. Para lograr lo que soñamos, pasando por diferentes etapas de la vida y después de todo lo construido, en la vida empieza a quedarse de nuevo aquí mismo. En la tierra nosotros vamos perdiendo nuestras energías, hasta volver de donde venimos. La vida solo es una oportunidad de poder disfrutar de ella, lo que nos ofrece y así poder encontrar felicidad cada persona”.