14 Reflejos del Cambio en la Memoria:

Obra reciente de Antún Kojtom y Kayum Ma’ax

En esta exposición, Reflejos del Cambio en la Memoria, damos a conocer series de obra reciente de dos maestros de la escuela maya chiapaneca: Antún Kojtom y Kayum Ma’ax. Están en diálogo sobre los mundos socio-estéticos que habitan, sobre los pueblos mayas chiapanecos, con profundísimas tradiciones, y en procesos de cambio radicales. Pintan sobre ayer, hoy y mañana, pero desde una cosmovisión donde el tiempo es una sonrisa sobre lo eterno.

Cada uno se aplica al lienzo con singular energía, Kojtom con un gesto grande y coloración de alegría; Ma’ax con una concentración al aplicar la pintura con pincel fino, para realizar su intensa configuración del detalle. Los dos artistas han participado en la escuela gráfica maya desde los momentos históricos en los años 80s, con talleres e intercambios entre los jóvenes pintores y grabadores de comunidades de habla tseltal, tsotzil y un lacandón. Han seguido siempre con interés la carrera uno al otro, y ahora la vitalidad confluyó; juntos se animaron por exponer obras recientes inspiradas por la comisión de la Galería MUY. Decidieron pintar juntos en un mismo gran lienzo, y las formas que bailan sobre él, nos ponen en mente de un dueto entre músicos neo-bonampaqueros del hoy.

Antún Kojtom (Ch’ixaltontik, Tenejapa, 1969) aprendió y perfeccionó dibujar, pintar en lienzo y mural, y hacer grabado, mediante una práctica más de 35 años. Comenzó en su pueblo natal, de manera autodidacta apasionado, se desplazó a Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco y durante seis años se entregó al minucioso estudio de la técnica gráfica al participar con un colectivo de artistas; desde 1993 tiene su taller en San Cristóbal de Las Casas y hogar en Tenejapa donde se nutre de la tradición y vistas de su pueblo. Kojtom fue un fundador del grupo Bonbajel Mayaetik y fundó el taller Gráfica Maya, “bajo los objetivos de promover el arte como medio de transformación social y la recuperación del conocimiento ancestral de los Pueblos Mayas”. También en las palabras del Maestro Antún:

Cada día que pasa voy descubriendo nuevos elementos, y uno de los más importantes que he logrado entender es el ch’ulel, es decir, la energía vinculada a los cuatro elementos: tierra, agua, luz solar y viento.

Kojtom ha expuesto sus óleos, acrílicos, dibujos y grabados, de manera individual y en grupo, en Chiapas y otras partes de México, en Estados Unidos y en Europa.

Kayum Ma’ax (Nahá, selva lacandona, Ocosingo, 1962), distinguido con el Premio Chiapas en 1992, tiene más de 30 años en la práctica del arte como un pintor orgullosamente autodidacta – quien ha aprendido de su inspiración por la naturaleza animada –, y quien ha logrado el reconocimiento del mundo artístico chiapaneco y mundial por su técnica inspirada y la profundidad espiritual de sus creaciones. Kayum Ma’ax, hijo del líder histórico el difunto Chankin Viejo. El creció en el entorno de una familia de gran cultura lacandón, hoy Ma’ax es reconocido por su enorme acervo de conocimientos de la tradición oral y la sabiduría espiritual de su pueblo. Los temas de su pintura giran alrededor del “jardín” selvática que es la selva lacandona, es decir la relación de los seres humanos, animales, seres divinos y la tierra. Todos sus cuadros son dados por los poderes, al explicar su práctica Kayum Ma’ax, y se permiten comparar con las imágenes narrativas de los códices mayas.

No es demás comentar que el maestro Kayum emana una felicidad liberadora en su manera de vivir y relacionarse, con un sentido del humor marcado, lo que se transmite en su obra pictórica, sin duda.

Ma’ax ha expuesto sus óleos y acrílicos de manera individual y en grupo, en Chiapas, la ciudad de México, Miama, EEUU, y Madrid, España.

Los dos creadores se fascinan por el arraigamiento de la localidad y su deslocalización por los tiempos y fuerzas mayores. Las figuras pintadas usan la vestimenta tradicional y localizadora de los pueblos de origen de cada uno. Se sienten en su dimensión genealógica, en la civilización maya, que es a la vez cotidiana y totémica: los hombres y las mujeres enfrentan sin mediación el jaguar que es sol, la mujer que es luna, y otras composiciones arquetípicas que trazan la línea entre lo local y lo universal.

Pero el mundo está deslocalizado ahora – estamos hablando del lamentado “cambio” en la boca de toda gente tradicionalista, y el enfoque de esta exposición en la Galería MUY. Asume su real faz de la colonización histórica y nueva. La opresión de las conquistas es palpable, tanto la española hace más de quinientos años como la del capitalismo que les robó gran parte de sus tierras y el neoliberal consumista de hoy, que puede ser la más invasiva, por ser deslocalizante desde adentro. El habitus para Ma’ax es peligroso, para Kojtom está enfermo.

Finalmente la atracción de este diálogo es su fe en la regeneración. En la obra de Ma’ax, la regeneración vegetal nos renueva la imaginación y esperanza; en la de Kojtom la regeneración civilizatoria, simbólica, nos instrumenta para inventar autonomías contemporáneas inspiradas en las de los mayas, y viceversa, ya que Ma’ax es igualmente simbolista y Kojtom comprometido con la ecología profunda. Este es un diálogo entre tseltal y maya, de proyectos locales y del maya-universal.

Estamos frente el arte político-espiritual. Kojtom y Ma’ax demuestran que el papel del artista es de ocupar tal campo con confianza, valentía y humildad.

Curador: J Burstein

11 de diciembre de 2015

Artworks

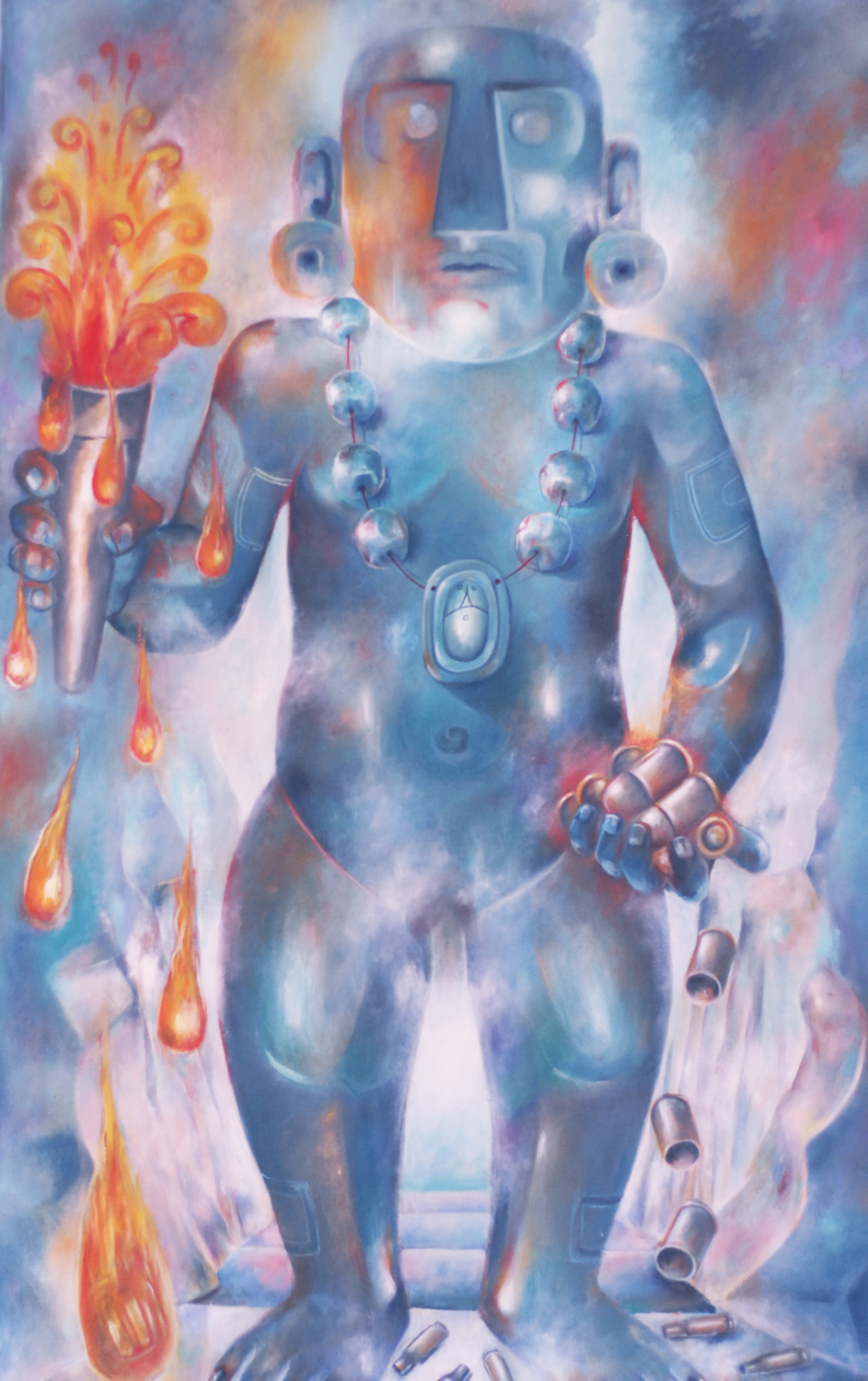

Upixan K’ax (The heart of the world) | Kayum Ma'ax

Acrílico sobre tela

150 x 100 cm

2015

“El corazón da la vida a todo el mundo, el sol nos da luz. El señor (a la izquierda) es Bor, el abuelo. Pide al señor del mundo y el señor toma el aspecto de una persona chiquita que reza por la costumbre, el hace su ceremonia. Vino un río y el agua entró en la olla que tiene alcohol, toca sus pies y vuelve a salir otra vez. Son lágrimas”.

“Las mamás son la madre tierra que abrazamos. Si no te abrazan, no vas a estar aquí. El hombre que agarra la cerveza, él es muy otro, sus pies se vuelven raíces; está equivocado porque no era de su costumbre. La ofrenda al jaguar, no está equivocado. El jaguar tiene ojos para mirar el corazón, mirar el mundo. Los dos armadillos: el primero trae maíz, dice nosotros comemos el maíz. El otro armadillo: yo traigo la muestra del frijol, que es número uno también, porque vivimos en la tierra. Se come con el maíz”.

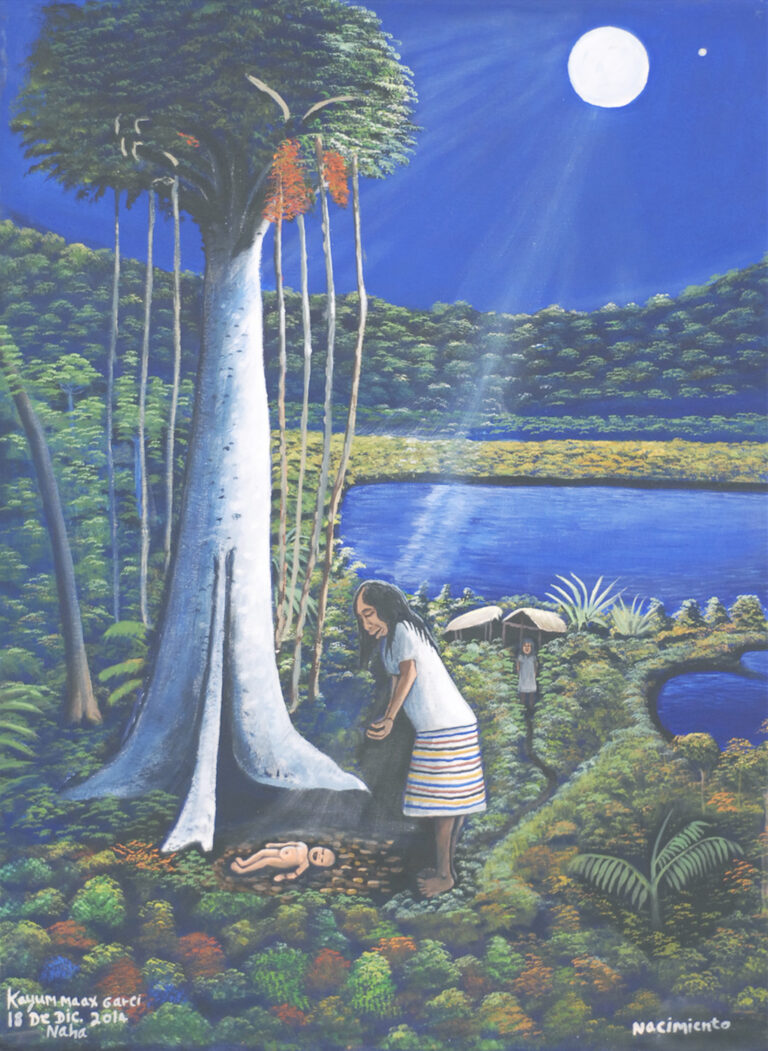

Birth | Kayum Ma'ax

Acrílico sobre tela

84 x 64 cm

2015

También tiene significado, “La selva dando la vida” Va a dar luz, la mujer encuentra la ceiba, no encuentra las papayas. No hay partera, no hay quien, porque viven solos, entonces en este tiempo hace mucho no nacía directo. Entonces, el bebé nace en tronco de la ceiba. La ceiba es sagrada. Cuando siente dolor, se va a la ceiba, se quita el dolor y nace el bebé en el tronco de la ceiba.

Winiki k’ax (The owners of the jungle) | Kayum Ma’ax

Acrílico sobre tela

150 x 100 cm

2015

“Los dueños viven en la selva, su casa es en las cuevas. No destruyen, no cortan, porque no tienen instrumentos filosos, sino piedras y lanzas no más. Los dueños son sus amigos de los monos y los saraguatos y el jabalí. Viven con sus amigos”.

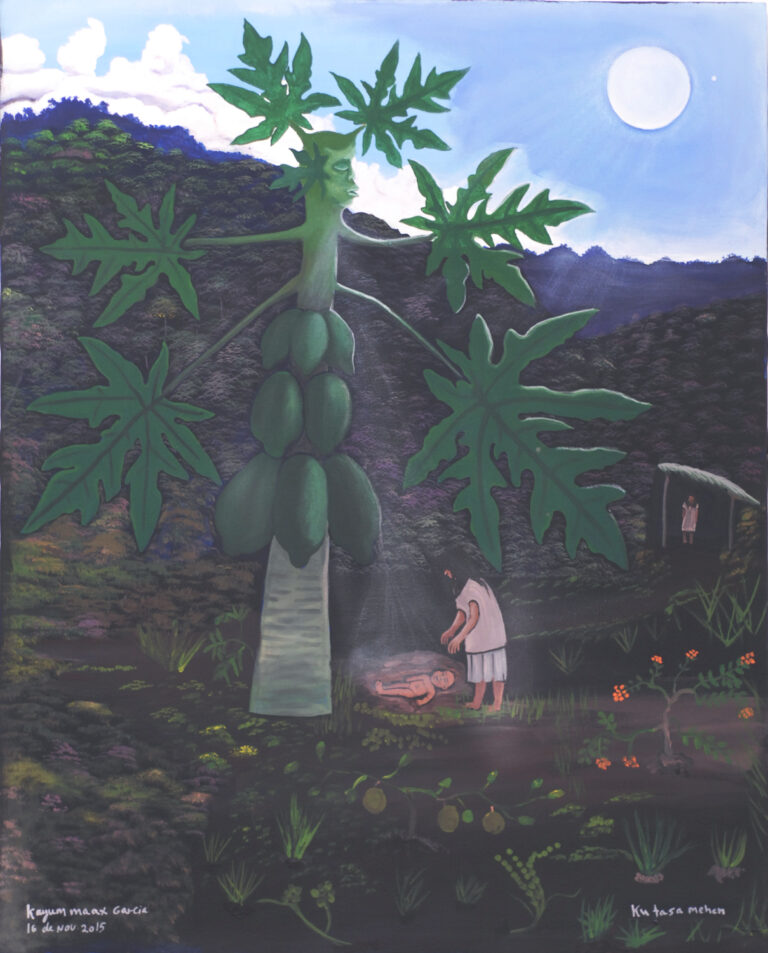

Ku tasa Mehen (Giving life) | Kayum Ma'ax

Acrílico sobre tela

100 x 80 cm

2015

“Las que están embarazadas se acercan a la papaya y nace el niño. No nace directo, porque la papaya traspasa el dolor. La papaya tiene chichis, es como mujer. Pero el niño no puede chupar porque tiene resina-veneno. Quizás antes no tenía resina, porque antes las mujeres no tenían pechos. Después de Cristo, ya cambió todo y los niños nacen directo. Aquí la papaya la está dando el niño”.

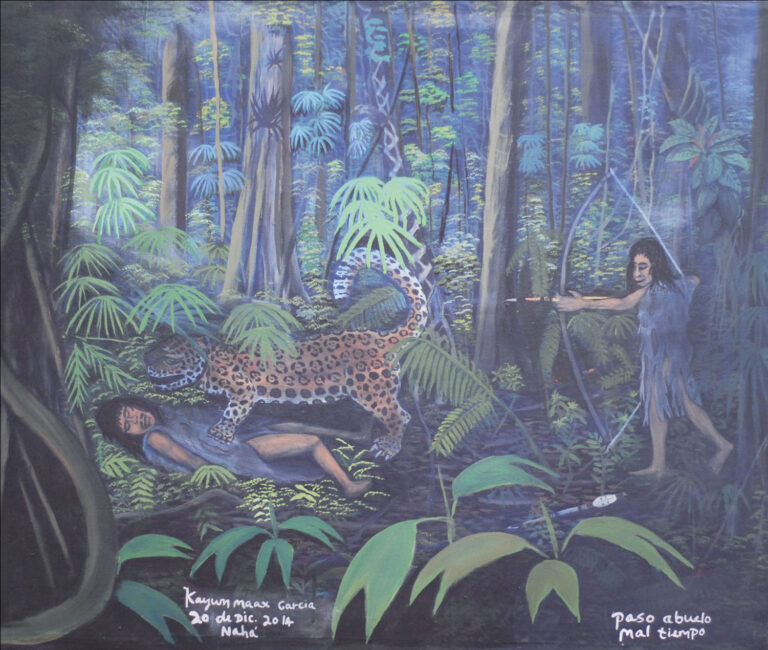

Grandpa passing bad weather | Kayum Ma'ax

Acrílico sobre tela

66 x 77 cm

2015

“Entraron los dos hermanos a la selva. Pero el papá le dijo a ese muchacho que no podían ir a la cacería, porque pasó su abuelo. No creyeron. Y allí una hora adentro de la selva atacó el jaguar, porque no le creyeron a sus papas. Es mal tiempo, dijo el abuelo. Fue el día martes que pasó el abuelo. En la naturaleza, pasan chiflando, es como un señor pasó, un mensajero de Dios; no se ve a él pero es cuando hay mal tiempo, o puede haber eclipse, o accidente con animales. Cuando escucha uno, entonces es malo. En maya el título del cuadro es Maneku“.

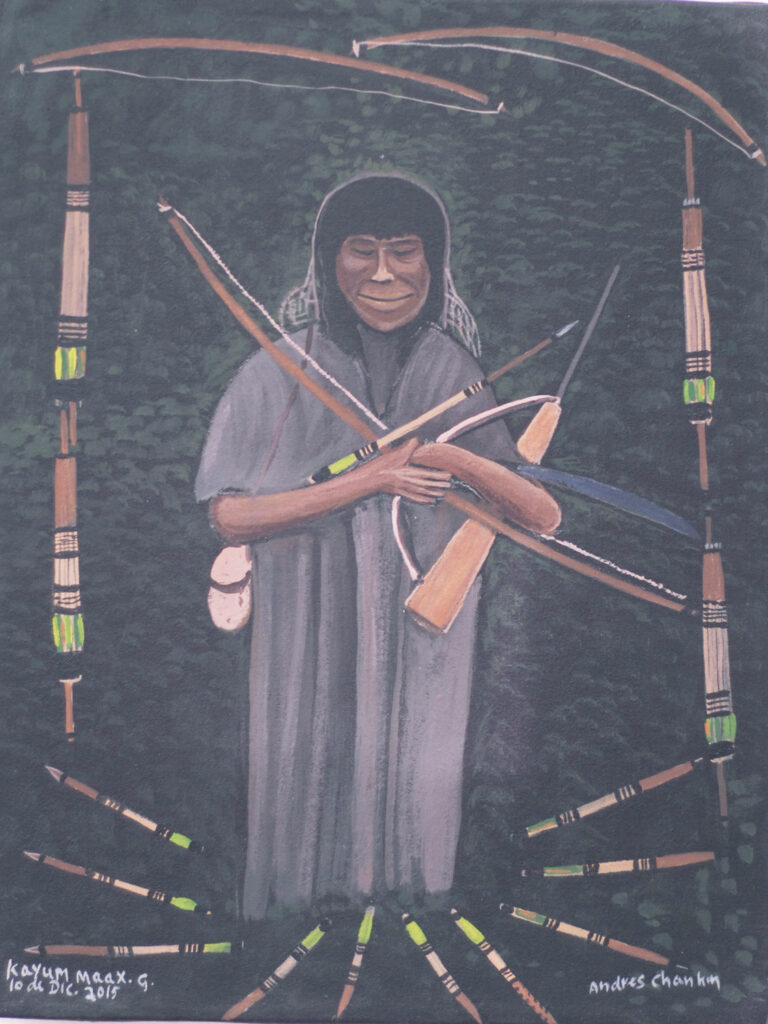

Andres Chankin | Kayum Ma'ax

Acrílico sobre tela

50 x 38 cm

2015

“Esta persona vivía en la selva, andaba sólo – Andrés Chankin –. No quería compartir a vivir como pueblo; sólo vivía con su familia. El tiene su rifle “cabaña 22”, pero él usa flecha, sabe usar flecha. Con los cambios ya tiene rifle y también las flechas”.

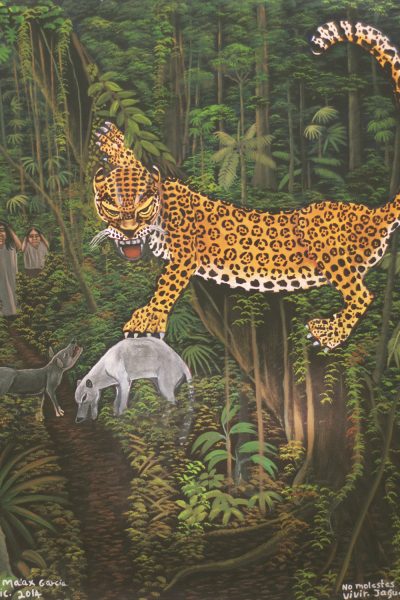

Don't bother, I want to live, jaguar | Kayum Ma'ax

Acrílico sobre tela

77 x 65 cm

2015

“El perro está diciendo: No molestes, quiero vivir, Jaguar. Los Hach winik traen muchos perros, y los perros cazan también a los jaguares. Pero el jaguar no quiere matar a los perros, porque quiere vivir, no quiere comer el perro. El quería comer venado o hasta vaca, pero no perro. Ellos van a la milpa, tienen varios perros, los perros ladran, el jaguar sube al árbol, pero agarra al perro porque huele al olor. Ahora el jaguar ya hizo cambio, ya no hay mucho, están protegidos los jaguares. Es bueno proteger porque son dueños de la selva. A veces no es jaguar, a veces es mascota del Señor (Hachakyum). El Dios del jaguar se llama Kanan K’ax, que vive en el ejido Sibal (del jardín dos horas en carro; es una ruina, y los tseltales lo están cuidando, es su Dios de ellos)”.

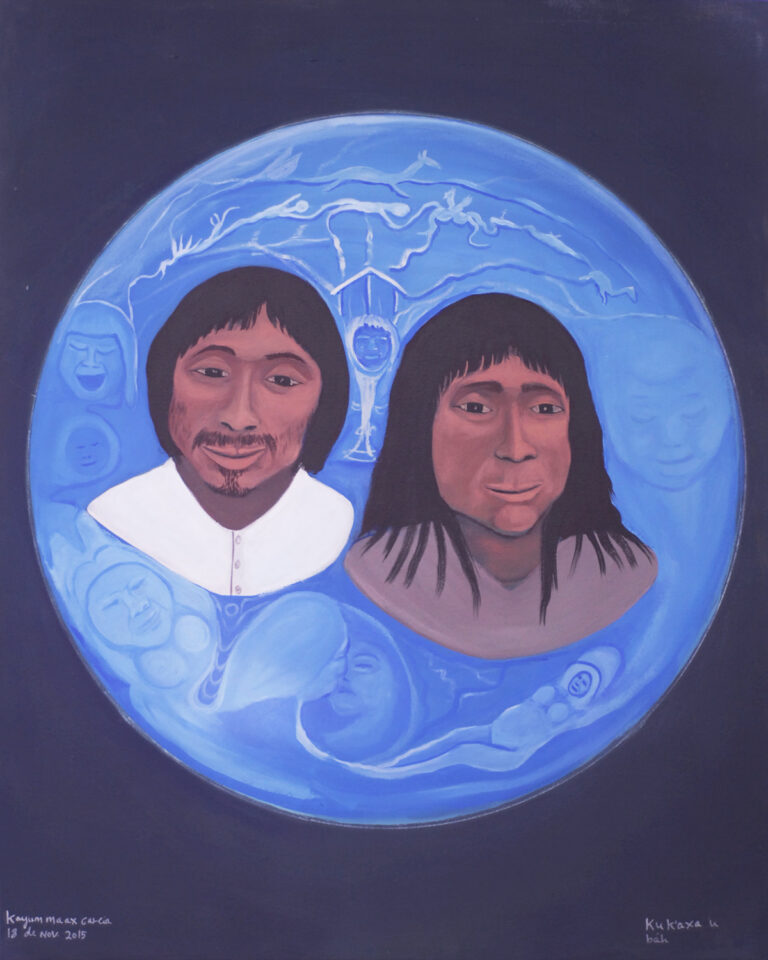

Ku k’axa u báh (Of the changes) | Kayum Ma'ax

Acrílico sobre tela

99 x 79 cm

2015

“Cuando yo era joven, así estaba yo (a la derecha). Ahora nuevo así (a la izquierda) como corté el pelo. Pero me volvió a salir. Atrás (en azul), son cosas del mundo. El mundo está triste porque está cambiando. Está acabando las lenguas, y los vestimentos. ¿Y por qué? Porque salen del pueblo – como Palenque o San Cristóbal –; ven cosas de otras personas – pantalones, camisas con corbatas – y previene del cambio. Los jóvenes van al pueblo y se encuentran con su pareja. Nosotros originalmente no besamos, ya vemos a los otros y la pasan besando. También el sexo trae enfermedades. (En la parte superior) son energías del pensamiento que dan vueltas pero no pueden hacer nada, hasta el fin del mundo”.

Analog connection | Antún Kojtom

Óleo sobre tela

129 x 86 cm

2015

“Todo el mundo habla ahora del apagón analógico. Conexión analógica es una reflexión de qué manera esta enchufado nuestra mente en la tecnología y mucho de ellos se recibe bombardeos de ser constantes consumidores de productos, la mentira, la violencia, el dolor, entre otras”.

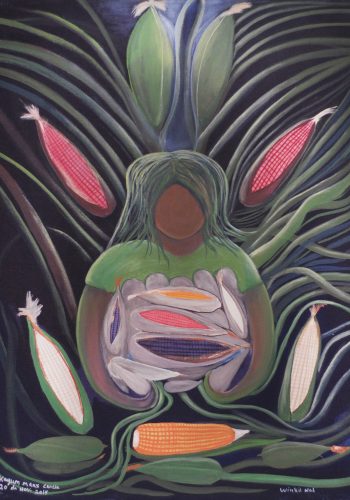

Winkil nal (Owner of corn) | Kayum Ma'ax

Acrílico sobre tela

70x60 cm

2015

“Este cuadro nos recuerda como Antonio, el maestro de la tradición esta con Kayum Ma’ax que quiere aprender y ya aprendió hacer el balché, el licor sagrado hecho de la cascara del árbol. Está sobre el cambio porque ya nadie lo hace. Ahora van al pueblo, ya compran aguardientes”.

Preparation of the Balche' ceremony | Kayum Ma'ax

Acrílico sobre tela

39 x 50 cm

2015

“Este cuadro nos recuerda como Antonio, el maestro de la tradición esta con Kayum Ma’ax que quiere aprender y ya aprendió hacer el balché, el licor sagrado hecho de la cascara del árbol. Está sobre el cambio porque ya nadie lo hace. Ahora van al pueblo, ya compran aguardientes”.

Ancestral memory thread | Antún Kojtom

Óleo sobre tela

120 x 60 cm

2015

“La relación entre, lo que es ahora y los ancestros me hace pensar en un hilo, y estamos al punto de desprendernos pero, finalmente vamos tejiendo nuestra historia. Ella está llena de luchas, desde la Colonia, antes, ahora y al futuro”.

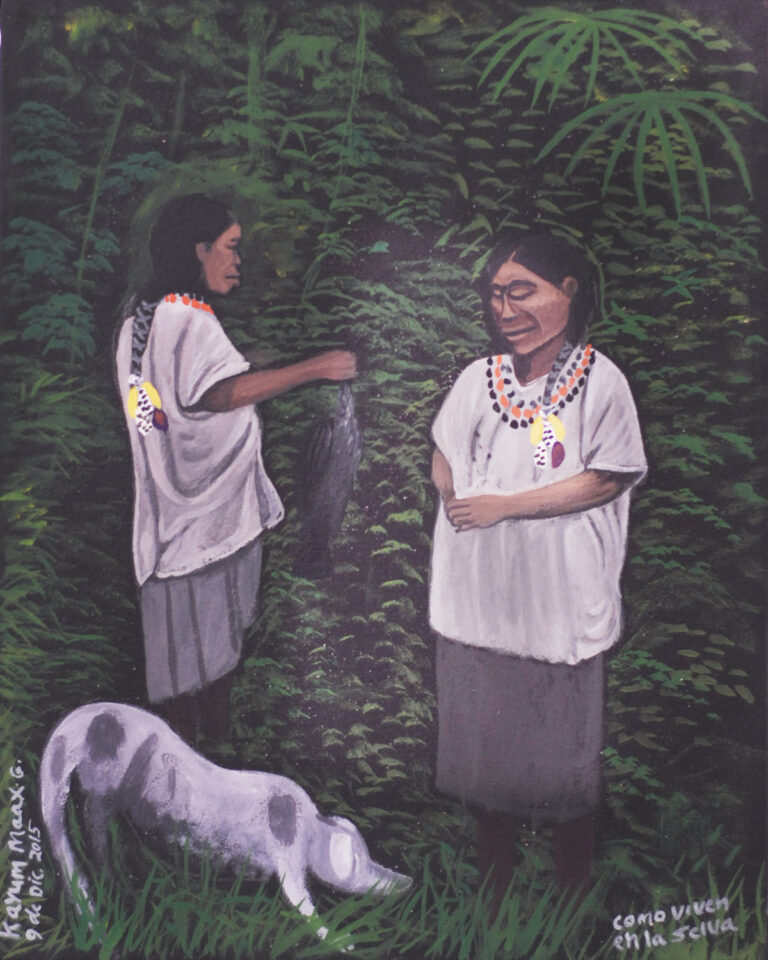

How to live in the jungle | Kayum Ma'ax

Acrílico sobre tela

40 x 50 cm

2015

“La verdadera gente como maya lacandón, su costumbre así era. Vivían adentro de la selva. Sus plumas son de tucán, y otros pájaros (como carpintero y colibrí); es la tradición de los mayas lacandones. Comían de alimento aves de la selva. Los maridos se casan, traen a sus mujeres para que coman, porque no conocen granjas. Nosotros comíamos cojolites y faisán. El perro tiene que andar porque los mayas tienen siempre. Los perros cuidan en el día, y en la noche cuidan a su dueño; no deja acercar los demonios”.

Woman with umbrella | Antún Kojtom

Óleo sobre tela

120 x 100 cm

2015

“Aquí las hojas se transforman en flechas y los tucanes se transforman en devoradores y la misma sombrilla se transforma en púas. Tal vez no tiene que ver con las promesas y la agresión del Partido Verde en Chiapas. ¿Qué es el verde?”.

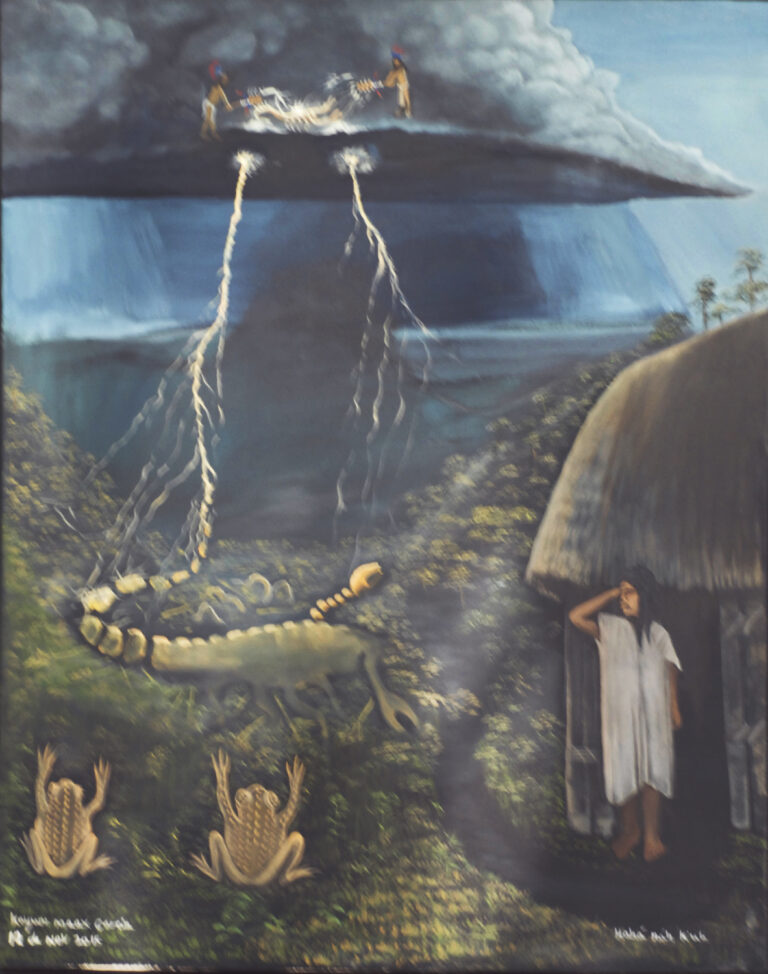

Hahá náh k’uh (The rays) | Kayum Ma'ax

Acrílico sobre tela

100 x 80 cm

2015

“Se tronó muy fuerte el 12 de noviembre. Tuve que hacer este cuadro. Es un problema por los espíritus de la naturaleza. Ellos están en las nubes. Ellos dos que están arriba se llaman jaja najkum; no los podemos ver, son dos hombres con su hacha de jade, ellos lo pegan entre dos. Sale el trueno. Los sapos sale rápido, dice “yo soy tu mamá” a los jajanaku, “párense, no truenan más”. Los rayos son espíritus, y tienen una casa que es una cueva muy profunda. De las nubes apareció un alacrán, o escorpión, pero son los espíritus”.