San Cristóbal de Las Casas. Chiapas, México

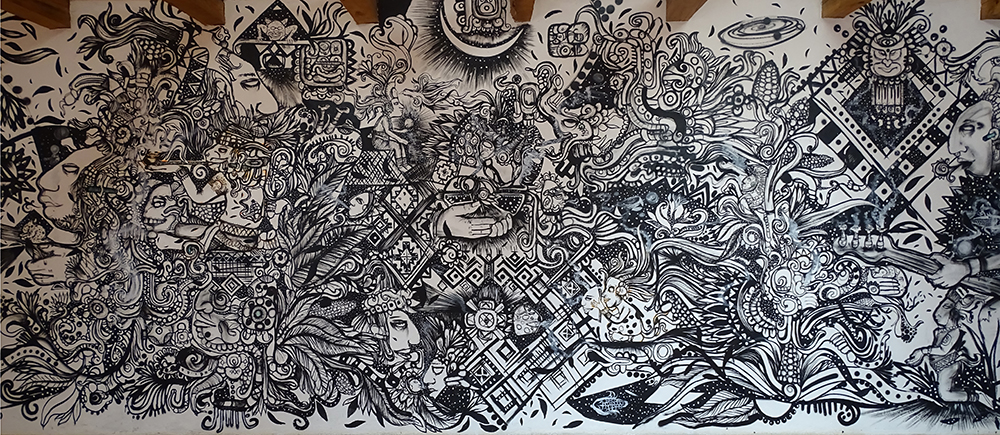

We celebrate the art created by more than 20 Maya and Zoque artists over the past eleven years of the Espacio MUY experiment: more than 30 collectively curated exhibitions, conversations on contemporary Indigenous art, workshops and murals in communities, and explorations in painting, sculpture, photography and video, installation, and performance.

“Exper-iment” and “exper-ience” both come from the Latin root meaning “to try” or “to test.” Each artwork is a test of communication through aesthetic media. “Muy”—our name and identity—is the root, in Tsotsil and other Mayan languages, meaning “joy,” “delight,” and also “to rise”: to raise one’s gaze, to experience positive or hopeful affect. This exhibition is very much an exper- of art.

These are communicative processes between people and between cultures. With creative genius—material skill and conceptual imagination—the works address fundamental themes in the lives of Indigenous peoples today: (1) gender equity and affective liberation; (2) the defense of territories (both geographic and cultural); (3) decolonial autonomy; and (4) spiritual ecology.

The permanent collection at Espacio MUY consists of works previously exhibited throughout the past eleven years, and in the curatorial process of “Eleven years may sound easy,” we selected 25 works from previous exhibitions that speak to the messages—in their respective media—that most move the artists and the audiences, both within and beyond their communities of origin. Logically, the catalog associated with this exhibition, Arte Hoy, is organized around the four principal themes mentioned above.

How can we capture and (re)experience the historic moments of MUY’s M/Z art? We present selections from the extensive MUY Archive, including documentation of community workshops, performance videos, and critical—and self-critical—discussion of Indigenous (local) art in relation to contemporary (global) art.

You are warmly invited to enjoy the three interrelated components—exhibition, catalog, archive—as an ongoing process of Maya/Zoque creativity in Chiapas.

Curators: John Burstein, Martha Alejandro, Emilia Sotelo, and artists.

artwork

K'ux peul | Maruch Sántiz

2016

Fotografía digital en papel de algodón

66 x 49 cm

Li k’ux peule ta spoxta k’ux ch’ut ik’etik, k’ux o’tonal lakanel

cha’pech yanal xch’uk jun litro ya’lel uch’bil. Li snich xtoke ta

xtun ta spoxil eilal, ti k’u s-elan ta meltsanele ta xich’ lakanel

li sniche xchi’uk jboch ya’lel mi sikube ja’ ta xich’ pokel o li eilale, mi jech sk’an ta xpoxtaj li eilale ta xlok’ ta anil.

White soda cures stomach pain and gastritis. Two leaves are boiled in one liter of water. The flower cures mouth ulcers; it is boiled in a quarter liter of water, and once cooled, it is used to rinse the mouth.

Ch'upak' te' | Maruch Sántiz

2016

Digital photograph on cotton paper.

66 x 49 cm

Li ch’upak’ te’e ta xtun sventa ta xich’ chik’el o, mi oy bu ch’iem chine, ja’ la ta syambe li sk’uxule xchi’uk ta st’omesbe ta anil li spojovile. Taje ja’ la ta xich’ k’okbel li yanal li ch’upak’te’e, ta xich’ voel ta k’ok’, va’i ja’ ta xich’ napbel li buy ipe, taje mu me xjalij ta xlok’ li spojovile ti jech ta xkol oe.

“Liquidambar is used to control pain and remove pus from pimples. The leaves are cut, heated over a fire, and applied to the pimple. They say the pus bursts quickly and it heals afterward.”

mother’s milk | Maruch Sántiz

2020

Series: The Proper Way to Feed Young Children

Digital photograph printed on baryta-coated cotton paper

17 x 13 pulgadas con marco

Ep lak’naetik labal ta xilik ti ta bats’i chu’il chve’ik li nene’ loinetike o vachetike, yu’un yepal no’ox ti chak’bik li manbil chu’vakaxe, li me’il li’e snopoj lek ti mu’yuk chak’be manbil chu’ile.

“Many of the neighbors are surprised that the twins are being breastfed, because society is very accustomed to giving artificial milk. This mother has decided not to give them canned milk.”

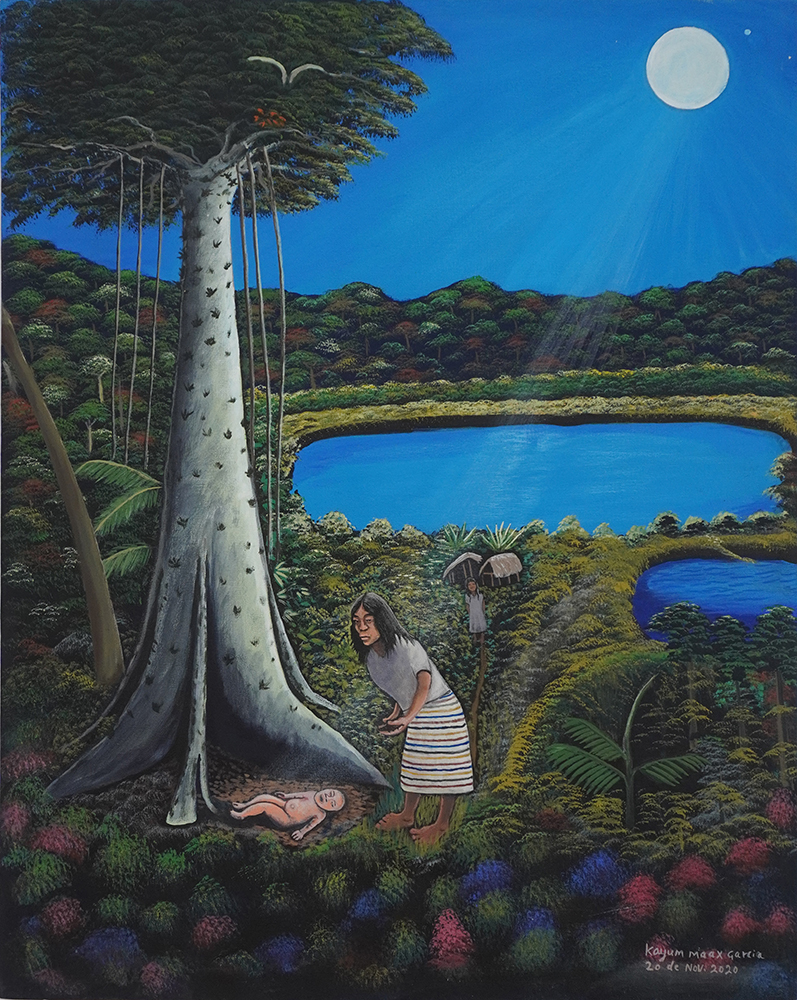

Birth | Kayúm Ma'ax

Oil on canvas.

84 x 64 cm

“It also carries meaning: ‘The jungle giving life.’ She is about to give birth; the woman finds the ceiba tree, she does not find the papayas. There is no midwife, no one around, because they live alone, and at that time babies were rarely born naturally. So, the baby is born on the trunk of the ceiba. The ceiba is sacred. When she feels pain, she goes to the ceiba; the pain goes away, and the baby is born on the trunk of the ceiba.”

Shipwrecked Worlds | Antún Kojtom

2020

Acrylic on canvas

104x104 cm

The idea came to me to create two ships that are installed on the ocean floor; they do not float, yet they attempt to move. The ship of death is carrying lung-trees, representing the life that exists in the countryside. It is the food that is brought to be sold in the city, the food we buy and eat, but it comes contaminated from the countryside by pesticides and herbicides. It carries lung-trees, but they do not represent life—they represent death. The industries claim to improve our lives, but they are actually making them worse. The poisoning of the earth brings consequences, and there are no methods to restore the health of the land. Therefore, it is a vessel moving in a different direction.

Meanwhile, the tree of life highlights our corn, which is a product that we have, and in some way the seeds of the foods that give life are still preserved— a tree with healthy lungs where the birds of our spirits can fly, flying in happiness, where the fish are also in harmony, while on the other side everything is chaos.

Aquatic Chaos | Alux Antún

2020

Acrilic on canva

50x60 cm

The artwork addresses what is happening today in the world due to industries that continue to grow and pollute lagoons, rivers, and seas. The sky is also being polluted by smoke and carbon dioxide—contaminated by human activity—causing life to slowly begin to collapse.

The fish being pulled represents the chaos that could occur if we continue polluting: all food and all living beings could start to perish. Animals will eat each other out of desperation, and this could also happen to human beings.

¿Bu oy ti lekil kuxlejale? (Where is well-being found?) | Säsäk Nichim / Abraham Gómez

2020

Digital photograph

60 x 45 cm

“The vast majority of Maya youth—and members of any linguistic community—have lost the notion of what lekil kuxlejal truly implies. When did the forgetting and denial of life in the countryside begin? Who told us that ‘good living’ is found in the city? Faced with this scenario of uncertainty and the captivity of life within concrete walls, the question remains: where is lekil kuxlejal, the ‘good living’?”

“We have become beings of machines, industries, and money. We destroy nature and no longer ensure the oxygen that is essential for good living. We have turned ourselves into a grafted form of life. Now the time has come to transform ourselves—to change our actions and the way we relate to one another. Let us replant our lives; let us sow creativity and art from nature in order to harvest a future full of hope.”

“This photo series calls on young people—those who already walk in two worlds, the city and the countryside—to continue the ancestral practices of our grandmothers and grandfathers: to keep cultivating the land, to avoid depending on agrochemicals, and to stop the ecocide.”

Carnival of Huixtán | Säsäk Nichim/ Abraham Gómez

Digital photograph

This photographic series is the result of a dialogical and collaborative interaction between the musicians and dancers who participate in the carnival and the photographers Margarita Martínez Pérez and Abraham Gómez Vázquez, members of the same Tsotsil linguistic community. All of them, as participants, have been involved in one way or another and form part of the event that is the carnival

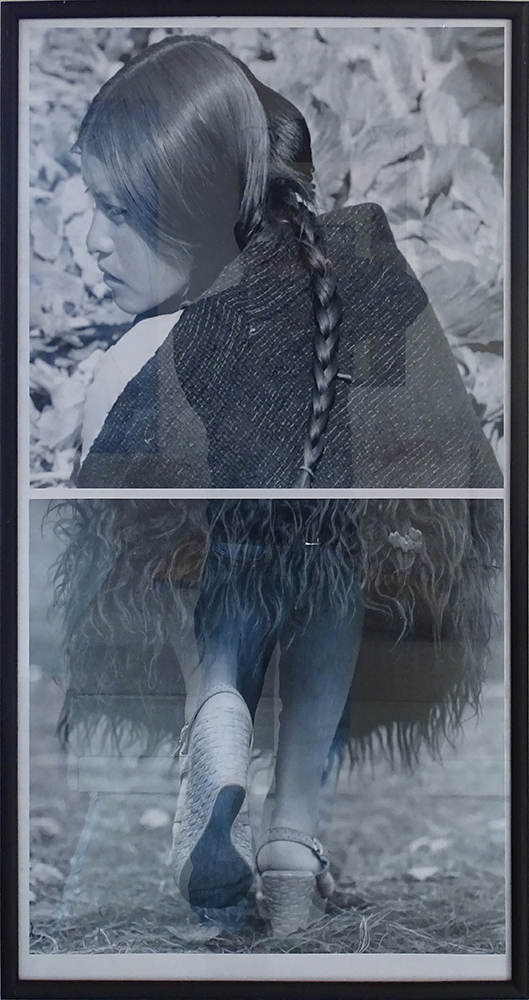

Symbol of consciousness | Pedro Gómez

2019

Terracotta

“In the town of San Andrés Larráinzar, women let their hair grow; the years go by and they do not cut it. Long hair represents beauty. When they hold a community position, they braid their hair and arrange it around the head; it is a symbol of knowledge and wisdom inherited from their ancestors, as well as a sign of authority. They are regarded with respect and addressed by the position they have held, for their strength in resisting and contributing to the responsibilities that the community requires.”

The rupture of the territory | Pedro Gómez

2018

Terracotta, wool, threads, and gourd

“This piece represents my town, San Andrés Larráinzar, which continues to be divided by political parties, religious beliefs, and the economy. Today, the thoughts of our ancestors—who maintained a united and strengthened community—are no longer embraced. Families reject one another and no longer communicate.

The chain and the lock represent the power that only a few people hold; they seek to lead the community as presidents or leaders of an organization, and they manipulate the town for their own benefit, without respecting the rights of women, children, or men. There is no longer awareness regarding health, education, or nature. As a result, the values of the community are being broken.”

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

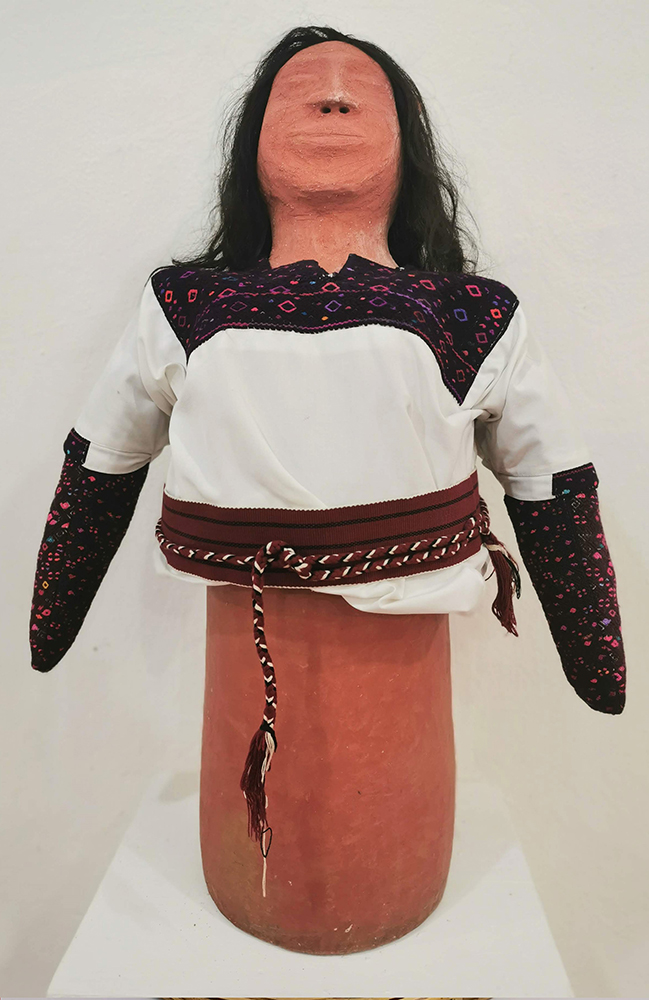

Me´xpak´inte´ (Mist Woman) | Pedro Gómez

2019

Terracotta and hair

“People in the town speak of the Me’xpak’inte’ (Mist Woman). She appears in the mountains when the fog descends, and she deceives men, presenting herself as a very beautiful woman. When a man is drunk, the Me’xpak’inte’ pretends to be his wife; in their unconscious state, the men begin to walk without direction. Their path becomes one where reality is no longer perceived, and they experience a beautiful imagination— a road filled with flowers and bright light. But the wonders come to an end, and they then find themselves surrounded by many thorny plants, in a dark and unfamiliar place, or she takes them to her cave.

In the dreams of their relatives, the drunk man reveals where he is, so they can rescue him before three days have passed. If not, they will no longer be able to recover him, because the Mist Woman takes them to another place.”

“The elders and those who know about the Me’xpak’inte’ say that when one goes out to gather firewood in the early mornings or in foggy evenings, it is recommended to turn one’s shirt and pants inside out, or to carry pilco (a sacred plant prepared to prevent being deceived by the Me’xpak’inte’ and the mountain spirits).”

Cube | Gerardo K’ulej

2026

Metal, stone

“The science and technology of the Maya have amazed me ever since I became aware of my origins. I must have been 13 or 14 years old, studying in middle school. I have always wondered: why is it that we, as Tsotsiles descended from the Maya, no longer hold the same knowledge to continue developing science? Did we stop observing and interacting with Mother Earth and the universe?

It is extraordinary how they were able to determine their calendars through the observation of the solar system and its closest planets. I would call the Maya ‘the scientists of light,’ knowledgeable about its properties and great geniuses in its manipulation, as can be seen in archaeology and in the study of their sacred buildings.

The construction of their pyramids had the purpose of capturing light to generate spectacular spectrums—phenomena they referred to as the ‘equinox’ and the ‘solstice.’”

Water | Cecy Gómez con Antonia Gómez

2019

70x180 cm

Cotton base, wool dyed with natural indigo (from Oaxaca), capulín dye (from Chiapas), and brazilwood; and wood

“This piece is a call to care for the rivers, the source of life. The zigzag represents the movement of the water. When there is a spring, it always seeks its own paths. Fish are food; if we do not take care of them, they become contaminated.”

Social division | Raymundo López

Oil on Canvas

“This artwork represents the social division of San Andrés Larráinzar through the metaphor of chess. In the past, it was a more united community, but politics can divide a people.

This division began with the armed uprising of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), and since then the community has split into two: the PRI supporters aligned with the government, and the autonomous group (EZLN).”

Painting the animals in the cave in my dream | Manuel Guzmán

Oil on canvas

“There is a cave near Chana’, and I can see it from my house. Water enters there, but before, it had a cross and people worshipped in the cave, and they called it an ‘angel’ in their belief. In Tzeltal the cave is called ik’al puyil (black conch/snail). I saw that they were painting deer in the cave.”

Woman of the Corncobs | Feliciana Ramírez

Sculpture made of fired and polished clay

“When I was a girl, there used to be very beautiful milpa fields, but now only a few people plant them.

We would go to shell the corn. Before, the stalks were very large; there were three or four ears of corn on each plant. There was no chemical liquid or fertilizer back then—just the hoe. The soil was mounded around the plants, and when the milpa began to flower, it grew very tall.

Now the corn no longer grows well; the ears are small. The chemical liquid burns the earth. Before, when they planted beans, the harvest was plentiful—now it no longer is. The beans sprout, but with little worms.

Corn and beans are very original and sacred. We ask God to give us an abundant corn harvest; that’s why there is a place for the candle.”

Mist Woman (Me’ Xpak’inté) | Maruch Méndez

Terracotta

One day, there was a man who was walking in the forest as he usually did, leaving his wife at home. Suddenly, he heard a woman’s voice in the forest. As he approached, he saw a lady on the path. She seemed to look like his wife. When he got closer, he heard her calling him, and feeling safe, he walked toward her. He walked into the forest until he became lost without realizing it, led by the xPakinté.