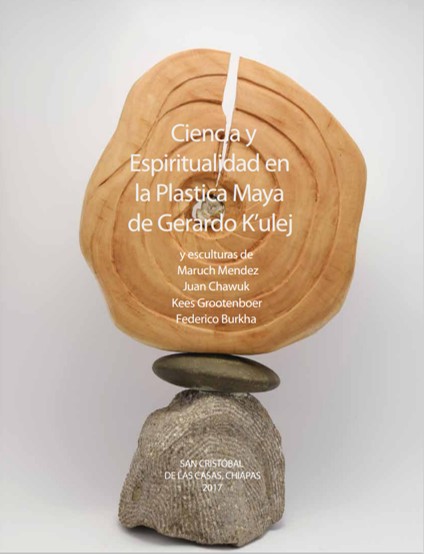

Sculptor Gerardo K’ulej, with additional works by his colleagues

El arte contemporáneo da una gran prioridad a la investigación. El artista investiga cómo los materiales de su empleo se pueden usar para profundizar en la investigación y juego de sus ideas. Y las ideas mismas se maduran y se hacen más complejas a través del diálogo de investigación compartida con otros artísticos. Esto define el campo de esta muestra de 13 esculturas de Gerardo K’ulej, y en diálogo con obras seleccionadas por él de artistas que le han influenciado o con quien está en diálogo con respecto al arte maya y universal.

Gerardo K’ulej es un científico entrenado como ingeniero bioquímico. Su investigación artística es también de la vida elemental. K’ulej nos muestra su genio para ingeniar estructuras, en formas altamente conceptualizadas, y cuya belleza nos abre el gozo, la intuición, y nuestra libertad a percibir la poesía en las cosas.

Es claro por qué el joven artista – nacido en 1988, y dedicado a su arte durante más de seis años – encontró en la escultura su medio. K’ulej es un investigador de las dimensiones. No satisfecho con las tres que vienen a la mano, y el cuarto, del tiempo, como esta exposición delimita, K’ulej se lanza en sus esculturas a representar dimensiones — como un físico de la teoría de las cuerdas — sin nombre y lleno de sensación y sentido.

Las y los espectadores leemos los textos de K’ulej y apreciamos los múltiples niveles de su investigación, incluyendo cosmología y cosmovisión, con su calidad evocativa y explicativa. Como parte de la instalación, el video (de Humberto Gómez que incorpora material de Francisco de Pares) da el punto de referencia desde su crianza en la comunidad de Chilil, Huixtán, sus investigaciones de la ciencia occidental/universal como estudiante del Instituto Tecnológico de Tuxtla, su inquietud por pasar del jardín donde trabajaba al estudio del escultor Federico Burkha, y su “retorno” a la cultura maya a través de su arte.

Como tsotsil-hablante se puso a investigar los viajes en las dimensiones misteriosas de un j’ilol de Chilil, curandero y sabio. En su investigación académica y artística ahora, retoma la matemática y la ciencia clásica maya – de la astronomía y arquitectura – y las contemporáneas, en particular como ingenieros de la biotierra (campesinos). Todo esto informa la obra escultórica de K’ulej.

K’ulej no presume únicamente inventar; al contrario su práctica artística es sumamente dialógica con sus maestros y colegas. Vemos las piezas seleccionadas por él de la escultora y curandera Maruch Méndez, quien acompaña con leyendas sus creaciones de lum que es la “biotierra”. Vemos las esculturas de Federico Burkha quien inspiró originalmente a K’ulej, y también su maestro y amigo Kees Grootenboer, cuya técnica se aplica a la arqueología inspirada en la cultura maya. Y apreciamos la selección de obra reciente escultórica del maestro Juan Chawuk, con samblajes “raros” (descripción del autor, con sonrisa), que se juntan sinfónicamente.

K’ulej es un artista igualmente de identidad maya y comunidad universal, dialógico y comunicativo. Esto se aprecia tanto en la incorporación de textos en su práctica artística, como en la inclusión de obras de otros escultores importantes en esta investigación de la escultura contemporáneo maya. Finalmente, su deseo de “comunitarizar” la escultura le llevó a salir de los confines de la galería propiamente, a crear una pieza de arte del campo actualmente en la cabecera de Zinacantán.

A las personas que nos visitan en la Galería MUY ¡bienvenidas a la plática artística sobre la plástica maya!

Semblanzas:

Gerardo K’ulej (Ch’ilil, Huixtán, 1988), uno de los artistas más modestos y más talentosos de recientes tiempos, hizo y hace sus estudios formales en el campo de las ciencias y docencia de matemática (graduado del Instituto Tecnológico de Tuxtla Gutiérrez y fue profesor en la American School Foundation of Chiapas en Tuxtla), y actualmente está concluyendo un diplomado en la didáctica de las matemáticas y estudio sobre el empleo de la milpa con ciencia maya. Le interesa la introducción del arte contemporáneo en espacios de comunidad maya contemporánea y el empleo del arte maya en la docencia, además del diálogo con artistas plásticos y el mundo artístico en nuestra dimensión irregularmente curvada de este planeta.

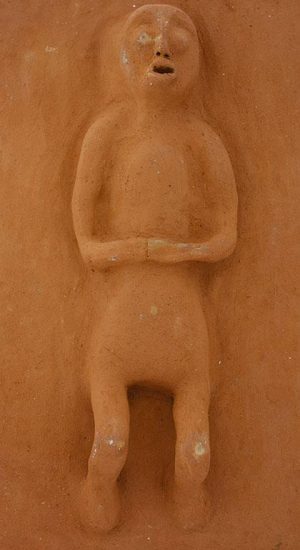

Maruch Méndez (K’atixtik, Chamula, 1957), artista multimedia, ha sido creadora en materiales de papel, tejido, y especialmente cerámica a baja temperatura, con narración y canto, con una larga trayectoria en Taller Leñateros y con la colaboradora, la poetisa Ámbar Past. Ha hecho performance y expuesto su obra en la ciudad de México, en Estados Unidos de A., y en París, Francia. En Santa Rosa pasada y frecuentemente solicitada para guiar los ritos chamulas.

Kees Grootenboer (Ciudad de México, 1942), escultor y pintor, quien ha trabajado como dibujante arqueológico en los sitios de Toniná, Lagartello, y varios sitios de Yucatán, residente durante 45 años en San Cristóbal de Las Casas, cuyo genio escultórico ha transformado la arquitectura de este pueblo con su distintivo empleo de la curvatura en la construcción de edificios, además de en su pintura y escultura.

Federico Burkha (Suiza, 1965) escultor de larga residencia en San Cristóbal de Las Casas y también en su nativo Suiza, quien ha sido premiado (Premio europeo de la actividad artística y cultural, 2012) y su obra expuesta en especial (Grands e Jeunes d’Aujoud’hui, Paris) en Europa y Chiapas.

Juan Chawuk (Las Margaritas, 1971), Tojolabal-hablante, estudió en La Esmeralda y principalmente autodidáctico, con una práctica variada basada en la pintura y escultura, además en performance y fotografía. Su obra está en colecciones importantes, incluyendo el Museo de Arte Mexicano de Chicago, y reciente ha tenido exposiciones en Kansas City, EEUU; París, Francia, Barcelona, España; y en múltiples ocasiones en la ciudad de México.

Curador: J Burstein

Agosto de 2017

Artworks

Self-awareness | Gerardo K'ulej

Madera y piedra

2017

“Me acuerdo del dicho: El hombre lo que hace en la vida, solo es reinterpretar las memorias del universo. Desde la partícula subatómica, hasta la galaxia, forman parte de un complejo estructural matemático. Tal vez para los mayas la matemática era una manifestación divina del universo, al entender dicha complejidad pudieron culminar con el avance matemático, con la invención del cero, el cero no como la representación del vacío, sino como la percepción de algo más profundo, como un ciclo repetitivo dentro de la naturaleza, ya que, dentro de las abstracciones del cero, se encuentra la concha del caracol y la forma de una flor.

Podemos observar dentro de la estructura del caracol formarse espirales, como si fuera un camino sin fin. O la flor dentro de sus estructuras geométricas con propiedades de repetitividad infinita”.

Evolution | Gerardo K'ulej

Metal, piedra y madera

2017

“El dinamismo del tiempo, la dualidad de destrucción-creación, de vida-cultura. Nacimos, crecemos y morimos: leyes fundamentales de la vida, como una estrella que nace, evoluciona y colapsa. Formación de un sistema solar, creación de vida, creación de culturas y por lo tanto la formación de diferentes concepciones del mundo, resultando una estructura de la realidad con base a paradigmas funcionales. Tal pareciera que la dimensión donde vivimos fuese como un tablero de ajedrez, donde el tiempo se ha encargado de acomodar las piezas. Antes de esta propia realidad moderna, existieron diferentes culturas, el cual ahora son sólo la memoria de nuestra propia creatividad. Puedo decir que la pieza tiene un metal de engranaje refiriendo al movimiento del tiempo, que si bien sin el humano, posiblemente tenga un sólo propósito evolucionar. Por ello la madera rompiéndose por la aparición de una nueva semilla. La duda: el hombre inventó el tiempo para explicar su evolución, o el mismo universo invento el tiempo para su propia evolución”.

Mut (Bird) | Gerardo K'ulej

Piedra de río

2017

“He viajado en diferentes lugares, en búsqueda de la paz interior, entre mi mente y espíritu. Los viajes se vuelven aprendizajes. Ecos de la memoria revolotean en cada montaña, montañas que guardan los espíritus voladores de nosotros los tsotsiles. Viajes de largas distancias aprendiendo de cada cultura, apreciando mi propia cultura, mi cuerpo se cansa, desmoronando cada plumaje del bello quetzal, ave de identidad de una cultura milenaria.”

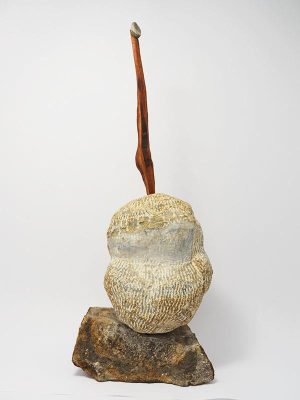

My father's verticality | Gerardo K'ulej

Piedra y madera

2016

“En la cosmovisión maya, se concibe que el universo está sostenido por cuatro pilares, que corresponden a los cuatro puntos cardinales. Podemos observar los pilares en la arquitectura de las casas de los tsotsiles, de una forma cuadrada, formando esos pilares para sostener el techo.

Como se lee en el Popol Vuh: La aparición y la relación del tiempo, lo que es en el cielo y sobre la tierra, la cuadratura de sus signos, la medida de sus ángulos, su alineación y el establecimiento de las paralelas en el cielo y sobre la tierra, a las cuatro extremidades, a los cuatro puntos cardinales, como fue dicho por el Creador y el Formador, la Madre, el Padre, de la vida.

Para los tsotsiles, los tatamoletic (abuelos) y membeltic (abuelas) forman un pilar; son quienes nos enseñan la responsabilidad de la vida y del trabajo en el campo. Los padres de cada hogar dan ideas claras y precisas que no pueden ser contradichas, porque es la autoridad. Si bien los padres son estrictos o duros en el sentido del regaño, ha sido para la formación del carácter de cada individuo. Por eso he construido la pieza con la piedra simbolizando el pilar como la autoridad inmodi ficable del padre, para la futura posteridad que se enfrenta a su vida propia”.

Cube | Gerardo K'ulej

Metal y piedra

2016

“La ciencia y tecnología de los mayas me han asombrado desde que tuve conocimiento de mis orígenes. Tal vez tenía 13 o 14 años y estudiaba en la secundaria. Siempre me he preguntado, ¿por qué ahora nuestra capacidad como tsotsiles provenientes de los mayas no tengamos el mismo conocimiento para seguir desarrollando ciencia? ¿Acaso dejamos de observar, e interactuar con la madre tierra y el universo?

Es extraordinario como ellos llegaron a precisar sus calendarios gracias a la observación de un sistema solar y de sus planetas más cercanos. Yo les llamaría a los mayas “los científicos de la luz”, conocedores de sus propiedades y grandes genios en su manipulación, como se ve en la arqueología y el estudio de sus edificios sagrados. La construcción de sus pirámides tiene el propósito de atraparla luz para generar espectros espectaculares en los que ellos les denominaron “equinoccio”, “solsticio”. Otra de las cuestiones tal vez importantes en el desarrollo de su especial ciencia es que ellos usaban una numerología vigesimal, como los dedos del individuo propio. Esta numerología les permitió generar sus calendarios, y darle de muchas maneras un significado útil a su numerología.

Aquí desarrollé una escultura de tres cubos de las siguientes medidas: 9 cm, seguido por 13 cm, seguido por 20 cm. El maíz necesita 9 días para salir de la tierra; nosotros como seres humanos necesitamos 9 meses de gestación dentro de nuestra madre. Ahora 13 por 20 son 260, y los 260 días son como 9 meses. Es decir, el número trece y el numero veinte en la compleja matriz del calendario de Tsolkin da un total de 260 días misma que forman los 9 meses. Me doy cuenta que estamos inmersos en un sistema de cálculos, que alguien sostiene para seguir con la generación”.

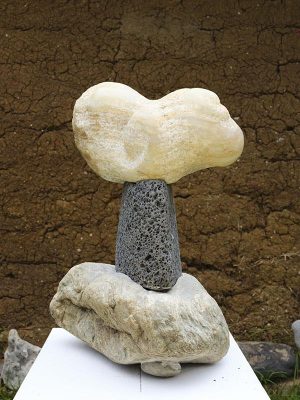

Flying spirit | Gerardo K'ulej

Piedra y madera

2017

“Hay cuestiones difíciles en la vida que pueden tomar una respuesta dependiendo del espectador. Lo cierto es que las piezas salen del subconsciente, de la intuición, de la armonía, de la exhaustiva búsqueda, o por el simple hecho de la casualidad.

El caminar implica la búsqueda de nuevos elementos, elementos que pueden ser parte de una idea o no, pero que al final puede manifestarse por sí mismos. Tal es el caso de esta escultura, sólo sé que me da pauta para explicar que percibo la energía de las diferentes dimensionalidades de los mundos, físicos y espirituales. La alteración de un cuerpo viajando por las diferentes dimensiones o los llamados mundos paralelos. Tanto en la concepción de los mayas, como en la ciencia moderna, se ha identificado la existencia de diferentes espacios donde la materia puede viajar. La única diferencia es que los mayas llegaron a alcanzar los denominados viajes astrales, por lo que la pieza trata de manifestar estos viajes en diferentes cuerpos, dejando una forma en cada espacio”.

The flower that is born | Gerardo K'ulej

Piedra y madera

2016

“La causa y el efecto, dos elementos que parecen estar presentes en todo en la vida; algunos hablan del destino, otros solamente de la suerte. En este caso, yo me topé con una piedra, mientras caminaba, que en primera instancia no tenía importancia, y no me llamó la atención. Cuando me acerqué a observarla, pude notar que tenía elementos de mucho interés (color, textura y forma). Con las ansias de querer trabajarla, decidí llevarla al taller. Tomé el cincel y di el primer golpe, después otro. Después de un rato mis ojos quedaron pasmados por la forma de la piedra. Siempre hay que buscar la belleza interior. Pero entre más belleza quieres conseguir requiere del tiempo y la paciencia y la posibilidad de socializar el trabajo, de dialogar con los demás. Cabe mencionar que no es la búsqueda de la perfección sino de la concientización”.

Cosmic game | Juan Chawuk

Madera, residuos orgánicos y pintura

“Las gentes de la comunidad ponen cruces cerca de los ojos de agua como protección y bendición. Está cubierto por vegetación, pero es el nacimiento del agua. Está regido por la fuerza de la luna, hay un ciclo lunar. Es un poder de energías, incluyendo las piezas de ajedrez, así que se convierte en un juego cultural. De dar y recibir; la naturaleza da el agua y nosotros damos la bendición. Es un juego constante de la vida y la muerte. Es la fusión del cristianismo y las creencias de los antepasados”.

The hand | Juan Chawuk

Madera, material orgánico

“Las manos simbolizan la acción física humana. Con las manos podemos contener la reverencia, lo sacro, lo profano también. (Es decir, en la Conquista, los españoles pensaban que las creencias de los nativos de este continente, su método de relacionarse con el ser superior, era muy profano, irreverente.) Es la fusión de la religión occidental y la nativa”.