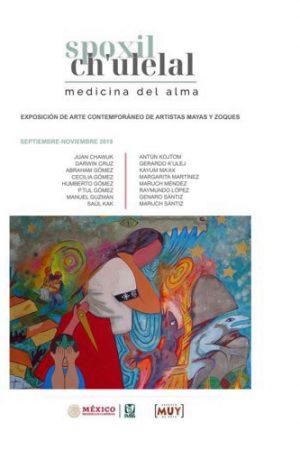

Spoxil Ch’ulelal: Medicine of the Soul brings together artists who speak five languages originating from the Mayan and Zoque families, from the state of Chiapas, who, from the new indigenous art, invite you to learn about their proposal on health, a holistic concept in which they integrate aspects of the physical, spiritual, natural and sociopolitical.

More than 40 works of painting, photography, sculpture, video and installation are shown here. They have been carried out by 16 women and men, with different circumstances – some self-taught and others trained in the academy, with a long or shorter career – who together interact on problems and relevant findings for the double look: inside and outside the town, approaching a vision of multicultural Mexico.

What does this new indigenous art consist of? It alludes to their cultures and the rest of Mexico, to the ancient Mayan cosmogony and its rescue through current art. The new indigenous art reflects a dual thought, with expressions of renewal accompanied by resistance, use of new media with recovery of tradition, autonomy in the face of globalization with intercultural hybrid identities. The new indigenous art expresses its freedom with media experimentation, and its commitment to the ancient wisdom and innovative genius of peoples.

Today’s indigenous artist is an ingenious creator with a disposition towards the multimedia and collective, and due to his functions, he is both an interpreter and a representative of his culture. In this way, the original artists are heirs to the traditional role of healers: they heal with art.

Spoxil Ch’ulelal It brings together works by well-known painters and pioneers of the new Mayan art, such as Kayum Ma’ax (Nahá, 1962), Juan Chawuk (Margaritas, 1971) and Antún Kojtom (Tenejapa, 1969), who have revolutionized concepts of visual culture. These concepts have been taken up by more recent painters and sculptors such as Darwin Cruz (Sabanilla, 1990) and Raymundo López (San Andrés, 1989). Artists with more intuitive but brilliant practices also participate, illustrating myths and dreams, such as Maruch Méndez (Chamula, 1959), P.T’ul Gómez (San Andrés Larrainzar, 1997) and Manuel Guzmán (Tenejapa, 1964). For her part, Maruch Sántiz (Chamula, 1975), defines contemporary photography made by indigenous subjects. Multimedia artists with varied approaches to “sociopolitical art” include Saúl Kak (Guayaval, 1989), Genaro Sántiz (Chamula, 1979), Abraham Gómez (Chamula, 1977), Humberto Gómez (San Andrés, 1988), Margarita Martínez (Huixtán, 1980 ), Cecilia Gómez (San Andrés Larrainzar, 1992) and Gerardo K’ulej (Huixtán, 1988). Together they break traditional art schemes with funny, critical, transgressive, proud attitudes and made with love for their personal and collective identities.

The realization of this exhibition has been possible thanks to the collaboration of the Mexican Social Security Institute with the MUY Art Space Gallery. The works belong to the MUY Gallery collection and to the personal collections of their creators.

Artworks

Sanitation with nature

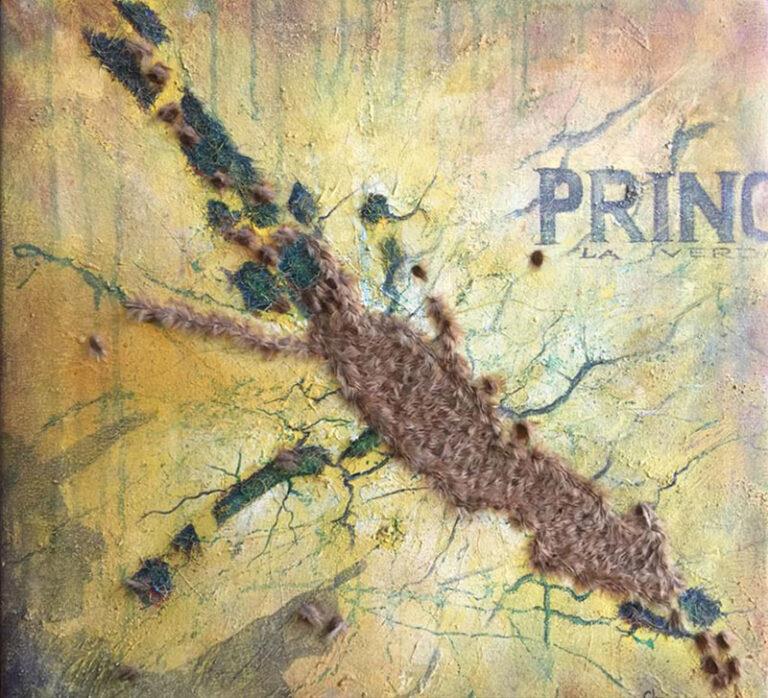

Flags

Gerardo K'ulej

Cloth and stamped

2019

The installation consists of nine flags, such as the months from planting to harvesting the corn, such as the months of human gestation.

Let’s celebrate the men and women of the corn!

“I am aware that the knowledge of the past may not seem to have as much meaning today, but if we assume our reality as a three-dimensionality between the past, the present and the future, we would learn to listen and understand the messages of our ancestors. We are a new generation with transcendental demands for the future and aware that our origin gives us the greatest meaning of our lives”.

Grito ancestral

Antún Kojtom

Acrylic on canvas

250 x 200 cm

2017

“I use some elements related to the memory of the Tseltal people in Tenejapa. There are four chargers; when the earth shakes it’s because the porters get tired of one arm and switch to the other. I represent the tectonic plate with a graphic pre-Columbian design. The woman is the ancestral mother earth, with a desperate cry. In his right hand he holds the damage or wounds caused by oil extraction, wars, atomic bombs or deforestation. On the other hand, the earthquake that happened on September 7 with all the damage it left on the Coast and in Los Altos. Mexican society joined those pains, by giving a hand to help. I also represent the eye of mother earth, the eye of the plants; life begins to flourish and at the top there is a new house”.

Me' nikel (Trembling mother)

Maruch Méndez

Installation, with terracotta figures, painting, stones,

rubble, earth, wood and stalagmites

200 x 150 x 200 cm

2017

“The first beings were inside the earth, but they came out onto the face of the earth. We are here but we do not see that the goddesses of the earth are on the same face of the earth. They talk to the God in Heaven. There are devils inside the earth, they kill human beings. They can make it rain, but hard and long, eight days, and a lot of water. Then comes the tremor. But it doesn’t always kill us. When the earth falls, yes, it kills us. If the earthquake comes — it’s ferocious — and we immediately speak to the Earth Goddess. We ran out of the house. There are ugly animals — evil at heart — within the earth. They cause the tremor. The men who go out to the field, talk to God so that he protects them”.

Mother Nature's claim

Raymundo López

Acrylic on canvas

150 x 70 cm

2017

“It is based on the memory of the five children who died in Larráinzar in the landslide of a wall that had been damaged by the earthquake. I speak in a general way of the misfortune that happened everywhere, I put the root that means that mother nature gives us and takes our lives. He doesn’t see if we’re rich or poor”.

Tomal ch'ix (Thistle flower)

Maruch Sántiz

Printing on cotton paper

61 x 41 cm

2016

“Li snich tomal ch’ixe ta tun sventa spokobil jsekubil ta xich’ lakanel chabej oxbejuk snich ta jun litro ya’lel chvokan vo’ob minute, uch’bil jboch ta sob, jboch ta o’lol k’ak’al xchi’uk ta bat k’ak’al jun xemuna ta uch’el”.

“The thistle flower is used to deflate and cleanse the liver, cut 2 or 3 flowers with 1 liter of water, boil for 5 minutes, drink a cup in the morning, one at noon and one in the afternoon. Treatment is for a week”.

Feminism and healing

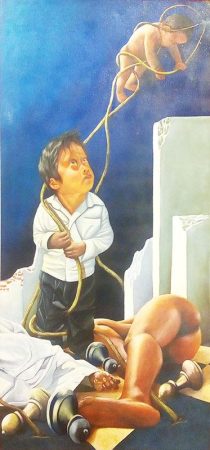

Oy jun vinik bat ta camposanto (The man who went to the cemetery)

Maruch Méndez

Acrylic on canvas

69 x 49 cm

2021

“There was a man who went to the cemetery, and leaving his pants and shirt, became a goat. Then he went to the house of a sick boy, jumped in while his family slept, and drained the sick boy’s blood until he died. He put it in a bottle, and gave it to the patron saint of the cemetery (the devil). Later he came with a friend who learned everything from the man-goat and between the two of them they treated a sick girl. But the first man was malicious and the friend ended up alerting the girl’s family. They killed that devil and the girl was cured.”

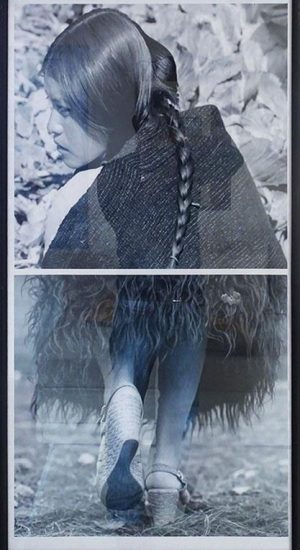

Stusaik lek stsots (Fixing the wool)

Margarita Martínez

Photography

56 x 71 cm

2018

“The hands intertwined with the threads stand out in a metaphorical way of how Tsotsil women weave relationships with each other, relationships of care with others, pulse and collective strength. Textile activities create conditions to collectively feel-think the power of the bats’i antsetik “true/original women”.”.

Awareness symbol

P.T'ul

Terracotta

2019

“In the town of San Andrés Larráinzar, women let their hair grow, the years go by and they do not cut it, long hair represents beauty. When they have a position they make a braid that fits around the head, it is a symbol of knowledge and wisdom experienced by the ancestors and a sign of authority. They are seen with respect and called for the position they have held, for having the strength to resist and contribute to the responsibilities that the people need.”.

Jal jkuxlejaltik (Life is long)

Cecy Gómez

Black cotton thread 16/2, cotton thread with ixtle, cotton and silk thread, banana stem fiber, yarn thread, loom auxiliary wood

530 x 50 cm

2020

“This piece represents life, the relationship with people in the community and city. The threads represent the blood that moves. Another symbol is that of the road, before there was no road, people walked on the sidewalks. The rhombus represents the center of the universe and the cardinal points. (Now through television, social networks, we have lost our values.) In the piece is the symbol of man and woman. There must be a reconciliation, a recognition — both are important — men and women can weave! Before they insulted the men who knitted, they said they are homosexual. But now there must be respect, it is an opportunity, there are discussions, a lot of criticism, there are men and women who are interested in textiles. There is also the frog symbol that represents rain and sowing in spring time”.

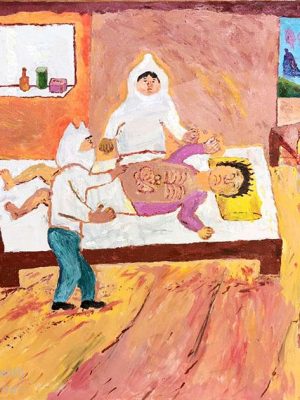

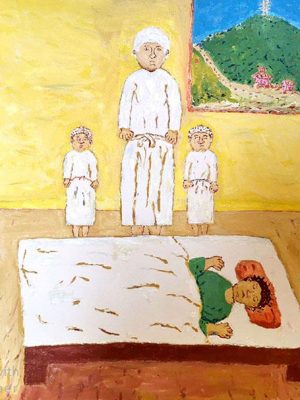

When I had surgery in the hospital

Manuel Guzmán

Oil on canvas

90 x 70 cm

2019

“Manuel, as a Catholic, fervently paints dreams and mythical and historical history with a traditional vision of the people under the gaze, protection and, on occasion, disapproval by the saints and God himself. “I painted the day of my operation, in the hospital where the doctors and nurses who treated me are, and I also painted the empty medicine containers”.

Jesus healed me

Manuel Guzmán

Oil on canvas

90 x 70 cm

2019

“The doctors told my relatives that I was not going to survive, because I could not eat. So my relatives looked for other people who would pray for me so that I would be cured. One day I saw Jesus with his angels in front of a sick man. After I saw Jesus my relatives fed me and I was able to eat, it took me several months to start walking. In their dreams, my relatives told them that I had an accident because I stopped receiving the host, but Jesus let me live”.

Spiritual healing

Ch’ulel II

Antún Kojtom

Óleo sobre tela

127 x 183 cm

2019

“Esta obra se basa en la cosmogonía maya-tseltal. Dentro de la obra hay 13 personajes que representan los 13 guardianes. Hay dos escenas de curación del ch’ulel (espíritu). Al lado izquierdo de la obra, el tipo de curación es una limpia con plantas, estas plantas pueden ser el hojo del pino (sabaltzu’unun). Aquí se usa el albaca. La función de la sanación con hierbas debe ser inverso: si es una mujer, debe de ser un varón quien le limpia; si es un varón que está enfermo tiene que ser una mujer que realiza la limpia”.

Piogbachuwe

Saúl Kak

Acrílico sobre tela

205 x 200 cm

2017

“Represento la madre tierra como la diosa, “Piogbachuwe”, que para los zoques representa la dualidad como el bien y el mal o la construcción y destrucción. En nuestra leyenda la erupción del volcán Chichonal (Chapultenango, Chiapas, 1982) está relacionada con la diosa Piogbachuwe; y la erupción se puede ver como positivo o negativo. Es como ella también provocó el terremoto del 7 de septiembre en Chiapas, para hacernos pensar y reflexionar sobre el actuar del ser humano. Tenemos que ser mas humanos… o mas animales: porque los animales no destruyen a la madre tierra, sino que conviven en su entorno. Hay un sistema estructural en el país, donde son solo unos cuantos quienes destruyen con sus sistemas de intereses y que la mayoría busca un bien para la buena convivencia con nuestro entorno.”

Traditional Balche ceremony

Kayúm Ma'ax

Acrílico sobre tela

100 x 120 cm

2018

“Antes no conocíamos el licor y tantas cervezas. Solamente hacían la fiesta, la ceremonia. Rezan por la familia y el mundo también, qué no nos enfermemos. Esta pintura representa la ceremonia del balche’, y pagos por los señores (piden ayuda al Señor del Cielo, Hacha’akyum). El balché está fermentado con miel o azúcar de caña; la corteza del árbol (a la derecha) se usa para tomar”.

Geometry

Gerardo K'ulej

Metal, piedra y madera

50 x 60 cm

2018

“De lo rectángulo a lo abstracto, una representación de la simplicidad de nuestro mundo, un lenguaje de la imaginación que cambia de una representación del mundo donde vivimos, una piedra anclada a la visión de nuestra tierra y toda la complejidad cósmica donde estamos envueltos”.

Sociopolitical sanitation

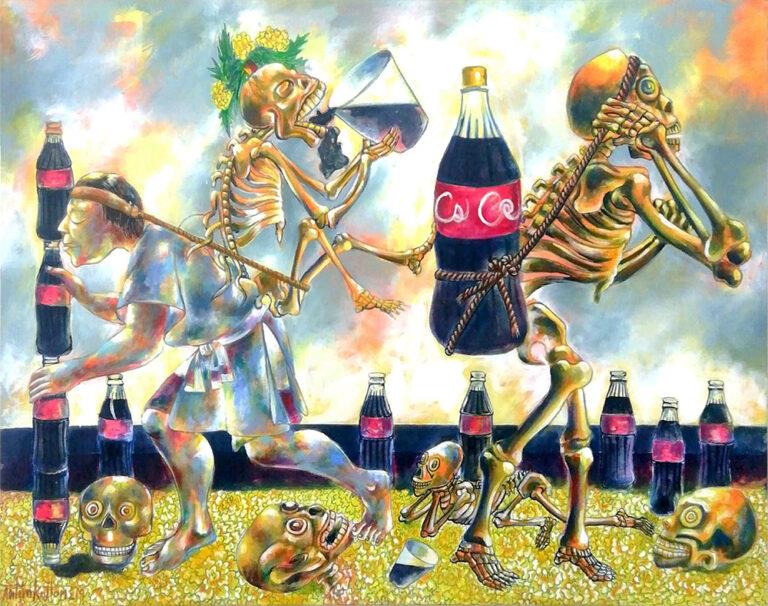

Drinkers' graveyard

Antún Kojtom

Acrílico sobre tela

70 x 90 cm

2018

“En Tenejapa sigue habiendo mucho problema de la enfermedad del diabetes. Mucho, mucho. La Coca Cola no deja de ser la bebida de los muertos. Le siguen ofreciendo a los muertos que prefieren ofrendarles como parte de su memoria terrenal. En la pintura además hay la muerte, cargado por tenejapaneco, que se anda burlando”.

The breakup of the territory

P. T'ul

Terracota, lana, hilos y tecomate

2018

“Esta pieza representa a mi pueblo San Andrés Larráinzar que se sigue dividiendo por partidos políticos, creencias religiosas y la economía. El día de hoy ya no se retoman los pensamientos de los ancestros que mantenían un pueblo unido y fortalecido. Las familias se rechazan y ya no se comunican. La cadena y el candado representa el poder que solo algunas personas tienen, buscan dirigir al pueblo como presidentes o lideres de una organización, manejan al pueblo a su conveniencia sin respetar los derechos de las mujeres, niños y hombres. Ya no hay conciencia por la salud, por la educación y la naturaleza. Eso hace que se rompan los valores del pueblo”.

From the series Bless my path

Abraham Gómez

Fotografía

50 x 37.2 cm

2017

“Aquí Gómez se impone una estructura “gramatical”: carros y camionetas en el centro de la composición con personas alrededor. Estas agrupaciones forman “frases” poéticas. La interacción entre fotógrafo y sujetos es complejo: son sus clientes, son sus compatriotas, y cada adquisición de carro representa una historia familiar fuerte. No solamente orgullosos por su compra, también son modestos, y por ello la selección por Gómez del título “Bendice mi camino” como un lema-nombre común a los vehículos en las comunidades mayas de Chiapas”.

Exhibition catalogue