¿En qué consiste la esencia, el genio, del trabajo de P.T’ul, y cuál es su orígen? Una imaginación muy libre y muy atada a las profundas tradiciones de su pueblo de San Andrés, Chiapas. Una seguridad humilde. Es autodidácto y por ello aprende de lo que sus mano enseñanan haciendo. Su inspiración se origina en el conocimiento de les mayas de la tierra, obtenido de la plática con sus abuelos/as, transformado en formas. De tierra, en primer lugar; ¿qué más natural? En pintura también; su pensamiento imaginario – a través del imagen – tiene de lo profético.

Pedro Gómez (San Andrés, 1997) viene de (y nutre a) una familia de artistas/artesanos enormamente informades de la gran tradición textil de San Andrés y la mayoría de les diez hermanas/os trabajan en el telar, en el diseño de obras artísticas adaptando la tradición, y en la difusión, comunicación y comercialización de su producción hecha colectivamente.

Al trabajar en esta exposición durante casi un año, P.T’ul vio como natural ampliar la muestra a objetos artísticos utilitarios, de sus manos, y de las de sus colegas en la Galería MUY: PH Joel, Martha Alejandro, Maruch Méndez, Darwin Cruz y Saúl Kak. El arte de contemplación y el arte utilitario están en diálogo constante. Si bien la inspiración para su arte escultórico viene de la vida práctica de su pueblo, objectos prácticos llevan lo estético en sus propias formas. Son prototipos de una nueva/vieja vajilla para la casa; ¿qué más práctico que comer? Y honrar los rituales de la producción campesina para la reproducción cultural familiar y comunitaria.

Para apreciar profundamente su cultura, a veces una persona tiene que alejarse de ella temporalmente. ¡P.T’ul salió de su casa a los siete años! Para recibir una educación bicultural en San Cristóbal de Las Casas. Nunca perdió su norte: el pueblo de San Andrés, como origen de su ser y su genio, aún cuando, con su propia familia, residen en Jobel (el San Cristóbal indígena). Es con estos ojos hacia adentro/desde afuera que logra pintar lo crítico y problemático, lo sufrido de las divisiones, las olas de explotación y las contradicciones de las modernizaciones. P.T’ul pinta las fragilidades de su pueblo.

Y moldea las formas de la esperanza, hechas por sus manos creativas indi-colectivas, originadas en ch’ulel maya/zoque.

Galería MUY

(curaduría colectiva dirigida por Martha Alejandro y Xun Tontik con PH Joel)

Diciembre 2022

Artworks

Cultural collaboration

Terracota

39 x 19 x 23 cm

2021

Es una pieza que habla sobre la unidad, donde las autoridades tradicionales colaboran todos a elevar sus voces para invocar el bien del pueblo. La curandera esta entre flotando entre la pieza, tan importante sanadora de físico, del alma, guía de los sueños y partera, las únicas que se ocupan para el cuidado de todos.

En la palma de la mano se encuentra la mujer, madre que procrea vida, da crecimiento, trasmite la memoria también conocimiento que da identidad comunitaria, la mano es la muestra de fortaleza que sujeta nuestra raíz de origen.

M’etik balumil (Mother Earth)

Terracota

42 x 21 x16 cm

2021

Una madre cargando a su bebé, él bebe representa al sembrador que ha llegado a la tierra para trabajar en ella, sembrar, cosechar frutos, tener comunicación y diálogo, le pone una mirada atenta hacia todas las señales naturales, como fuertes vientos, sequías, también cuando se le brinda ofrendas para sentirse apreciada.

El sembrador o campesino conoce todo lo que hay sobre el suelo y lo que guarda por dentro y la tierra conoce al hombre si está unido con su nahual el animal guardia que nos han sido proporcionados desde que nacemos. Una representación está el tlacuache se encuentra en el pecho y entre el vientre ahí donde se perciben señales de nuestro alrededor y nuestro estado de salud.

Musicians of life

Terracota

30 x 18 40 cm

2022

Es una figura cuadrada con cuatro patas, tiene dos personas con rostros de pájaros. Los músicos tradicionales acompañan a las autoridades del pueblo en cada ceremonia, en ciertas horas de la mañana, del medio dia y noche, tocan el arpa, la flauta, y el tambor, tienen un gran compromiso que son fundamentales para la cultura y para el pueblo. La personas tienen el rostro de pájaros, porque por las mañanas los pájaros cantan cuando el sol esta saliendo tiene un significado,cuando el sol se esta ocultando tambien cantan eso quiere decir que el sol ya se está despidiendo, los pajararos avisan, también hay otros pájaros en la temporada de lluvia cantan en grupos, estos cantos son un mensaje para la comunidad, hay cantos que avisan.

Legacy of grandparents

Terracota

37 x 37 x 41 cm

2022

Es una figura de dos personas que están unidos en la cabeza, en la parte de frente esta sosteniendo el maíz haciendo la representación de la entrega de la bandera dejando a las nuevas generaciones, y el joven de la nueva generación está conectado con la memoria y todo el conocimiento, que los abuelos tienen sobre la vida, tradición y la cosmovición. Para los abuelos es muy importante, que la nueva generación los escuchemos y se mantenga la práctica del campo de cosechar la comida, esto nos da identidad, vida, salud y nos nutre fisicamente y culturalmente.

Home Protector

Barro local de san Ramón y oxidos

26 x 23 x 14 cm

2022

Es una figura de un toro, arriba tiene una casa que le dice vakax na´(casa con estructura de un toro). En la comunidad cuando se construye una casa en medio se entierra la cabeza de la res, es para que cuando haya enfermedades y malas energias o el mal aparezca. El toro es el que tiene que defender a la familia en esa casa. En San Andres de donde vengo se tiene esta creencia, mis abuelos, mi familia lo siguen realizando aquí en Chiapas.

Day of the dead offering

Barro local de San Ramón y oxidos

25 x 27 x 27 cm

2022

Es una jarrón de tres patas, tie ne dibujos sobre la carne ahumada que se come y se ofrenda el día de muertos, tiene una calavera y otra persona donde le esta dando la ofrenda, los jarrones se ocupan para los tamales y atoles el día de muertos.

Transformation

Escultura, barro de la Selva

18 x 20 x 14 cm

2022

Se cuenta en la comunidad que cuando un ratón quiere transformarse en un murciélago, antes tiene que enfrentarse a las pruebas de la naturaleza, tiene que ponerse a la orilla de la carretera. Cuando esté pasando un carro tiene que cruzar con tres saltos para la otra orilla del camino, si logra cruzar entonces sera un murciélago, y volará por los cielo. Será un polinizador y distribuirá las semillas de las frutas. Pero si falla en dar los tres saltos, lo atropellan o se paraliza por miedo antes de cruzar, perderá la vida.

Eye

Escultura, barro local

27 cm x 24 cm

2020

Esta obra está construida atraves de iconografía de textiles de los pueblos mayas. Unidos sus puntos, figuran una estrella. Hacía el fondo hay un ojo, con una mirada grande; es él que cuida, observa e ilumina la supervivencia de los pueblos originarios cuando pasan en dificultades.

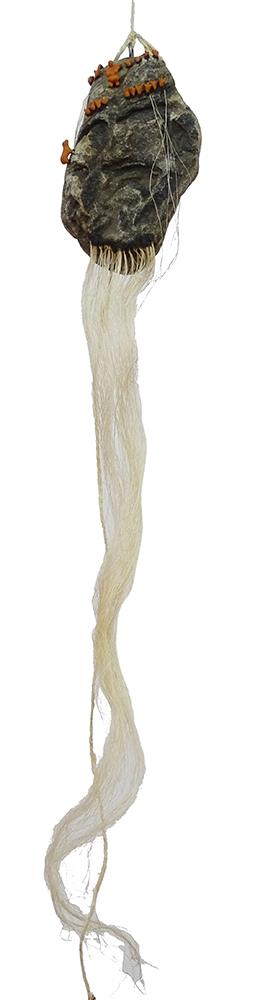

Ilchi (Shepherd)

Roca, cuarzo, espina de ceiba y figuras de barro

12 x 29 x 12 cm

2022

Esta pieza surgió de un recuerdo cuando mi abuela iba a muk´tabits (cerro grande) es un paraje donde vivieron mucho tiempo, es un cerro grande caminaba una hora y media para llevar a pastorear a sus borregos, llevaba a sus nietos para enseñar como cuidar los borregos, como cortar y sembrar las verduras, buscar leñas y visitar los manantiales de los cerros. Esto me hace recordar el sabor del agua que sale de las rocas, de los borregos formados en las veredas de cómo cuidarlos y alimentarlos, para tener una buena lana y con eso hacer ropas.

The sower

Piedra, fibras de maguey y barro

120 x 15 x 10 cm

2022

El sembrador es la representación del campesino que siembra la tierra, al medio día cuando llega a las doce, se sienta y observa sus plantas si germinaron las semilla. Es cuando aprovecha agradecer la vida, pide por el cuidado y bienestar de su siembra, porque es donde obtiene alimento y vida, de una manera de vivir, de llenar el hogar de comida.

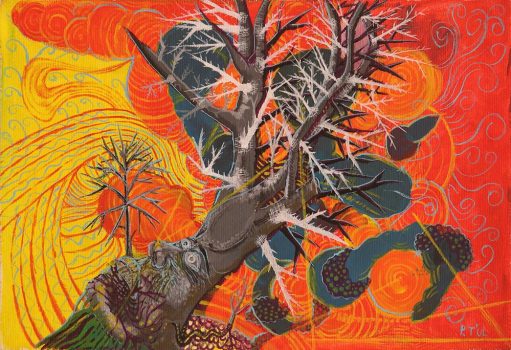

The shoot

26 x 18 cm

Acrilico sobre tela

2022

Hay árboles que al ser talados solo se queda el tronco y las raíces vuelven a retoñar, las ramas comienzan a crecer. Con los pueblos muchas veces se fragmentan ideológicamente, que impiden a una organizaciòn comunitaria, pero aún así aprendemos a seguir creciendo.

Kosilaltik (Our territory)

Acrílico sobre tela

28 x 26 cm

2022

Esta obra tiene la forma de una choza. En el campo lo primordial es tener buena cosecha, buenos frutos. A veces por la necesidad por buscar economía, migran hacia la ciudad, a los pueblos mas grandes, cruzan otros territorios, conocen otras culturas y otras formas de vida. Lo que les recibe es la dificultad con el idioma, y cuando viajan a otros paises en ocasiones pierdan la vida y encuentran una triste realidad que es la muerte.