San Cristóbal de Las Casas. Chiapas, México

Espacio Artístico MUY, A.C. (Espacio MUY / Galería MUY) will be present at Material Art Fair 2026, featuring works by three master artists of Maya culture and ancestry. Below, we share information about the artists and specific details of the works on view.

Espacio MUY— a project founded in 2014 and based in San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico—follow us on Instagram @espaciomuy and on Facebook @galeriamuy. You may contact us (attention: Director Martha Alejandro) through these platforms or by email at galeriamuy@gmail.com for inquiries and to be added to our mailing list or WhatsApp group.

We are part of a global movement that supports contemporary art created by Indigenous artists, and by subscribing to our newsletters, you too will become part of it!

Cecilia Gómez

Artista maya/tsotsil

(Chonomyakilo’, municipality of San Andrés Larráinzar, Chiapas; 1992). Her medium is textile art, in which she combines materials native to the land with pre-Hispanic dyeing and weaving techniques.

The value of Cecy’s work is twofold; both its form and its content are equally significant. On the one hand, the medium chosen by the artist helps prevent the disappearance of a millennia-old Maya tradition. The support itself is a political act, through which Cecy chooses to continue weaving the traditions of her community. On the other hand, through her art she reclaims a practice historically assigned exclusively to women. The weaver confronts the loom as a channel of contemporary communication. What is inherently hers as a Tsotsil woman has become her weapon as an artist, with which she transcribes messages that challenge the present.

Cecy is a creative researcher in natural dyes and the designer and coordinator of Tulan Textiles, producing unique pieces made on the backstrap loom. Her works have been exhibited at the Palacio de Bellas Artes (Mexico), Kates-Ferri Projects (New York), and the Museum of Art in Łódź, Poland.

Darwin Cruz

Artista maya/ch’ol

(Sabanilla, Chiapas; 1990) completed his studies at the University of Sciences and Arts of Chiapas (UNICACH). His works constitute a visual memory of the vast oral tradition he has gathered throughout his life, granting significance to the knowledge that has been preserved for generations through dialogue and interaction within his community. From this process, he extracts the key elements and protagonists that shape his pictorial work. Through oil painting and new digital media, he confronts the normalized behaviors of repressed realities that colonizing institutions have imposed on rural communities.

Darwin has received numerous distinctions, including recognition from the United Nations (UN Human Rights 2024 Laureate, International Art Contest for Minority Artists), an award at the First International Pictorial Triennial at CECUT (Tijuana), and, in 2025, the prestigious Jóvenes Creadores grant from FONCA (Mexico).

Gerardo K’ulej

Artista maya/tsotsil

(Chilil, Huixtán, Chiapas; 1988) is a multidisciplinary artist, a generative creator using computer-based programs, and a masters in bio-science. He explores his contemporary Tsotsil identity amid the multiple tensions of the “glocal” world (global–local), and defines his art as abstract bio-Maya. “My appropriation of technological resources is the path toward intercultural transformation, but always from my commitment to a Maya–Tsotsil futurist vision,” he says.

K’ulej earned admission and a scholarship to undertake an artists’ residency at the Banff Centre for Arts, specializing in Indigenous arts (Alberta, Canada). He has exhibited in Mexico City and other parts of Mexico, and also works in architecture and the construction of living spaces using natural materials.

Gerardo K’ulej (Chilil, Huixtán, Chiapas; 1988) es un artista multidisciplinario, creador generativo (con referencia a programas computacionales) y estudioso de la ciencia. Explora su identidad tsotsil contemporánea en medio de las múltiples tensiones del mundo “glocal” (global–local), y define su arte como bio-maya abstracto. “Mi apropiación de los recursos tecnológicos es la vía hacia la transformación intercultural, pero siempre desde mi compromiso con una visión futurista maya-tsotsil”, afirma.

K’ulej obtuvo el ingreso y una beca para realizar una residencia artística en el Banff Centre for Arts, con especialización en artes de pueblos originarios (Alberta, Canadá). Ha exhibido en Oaxaca y Tulum, y también se dedica a la arquitectura y a la construcción de espacios vivenciales.

Artworks

Star | Cecy Gómez

Mini balls of wool, dyed with natural pigments

90 x 85 cm

2026

The star brocade is part of our traditional textile art. I want to honor the people who relate the constellations to the seasons of the year. When I was little, I used to talk a lot with the stars. I asked them to take care of my little sister, who died when just a baby. Speaking with them gave me peace in my heart, by knowing she was in good hands.

Palms and Fish | Cecy Gómez

Backstrap loom with supplementary brocade, made with mercerized threads

70 x 190 cm

2025

I fell in love with palm trees the first time I saw them in Cancún, and I wanted to incorporate them into my iconography because their roots run deep. Fish carry the meaning of abundance in our culture. Fish and seas are at risk due to the pollution generated by human populations. Within them, many of the foods that sustain our lives are reproduced.

Traces of migration | Cecy Gómez

Balls of wool dyed with natural pigments

52 x 55 cm

2024

The largest ball of yarn represents the – more commonly –male head of the family; usually he is the person to leave in search of work. The person who migrants, though, always leaves traces behind and, many times, feelings of emptiness. He moves away from his community and culture and loses touch with the daily goings-on of the family. Now, women often have greater freedom; they seek an activity or even start a business, grow closer to their mothers, and find ways to move forward. Children may fall into vices, and that can become a problem.

In many cases, migrating is a decision of life or death: they cross the desert and arrive in a place completely outside their environment. For this reason, migrants also deserve respect.

The universe | Cecy Gómez

Backstrap loom with supplementary brocade, made with mercerized threads

70 x 125 cm

2025

The weavers of my community call this figure “the universe.” It reminds us that our ancestors deeply respected the connections—between individuals as well as between different communities—and even extending outward to the entire world. Our ancestors shared knowledge and life-ways among eachother, strengthening community bonds and collective support. The profusion of colors within the figure also makes me think about the many dimensional diversity among people.

Me' ts'i(Female dog)) | Darwin Cruz

Real banknotes, wood

38 x34 x10 cm

2026

This work is inspired by the Indigenous women street vendors who move through the streets of San Cristóbal de Las Casas.

With the increase in tourism and the designation of San Cristóbal as the cultural capitalof Chiapas, our knowledge and even our very image are instrumentalized for the accumulation of economic, political, and social capital. However, it is mostly intermediary companies that benefit, while creators face exploitation and discrimination—especially when they directly offer their work as street vendors.

In short, they are treated like dogs; this is why I titled this work “me’ ts’i’.”

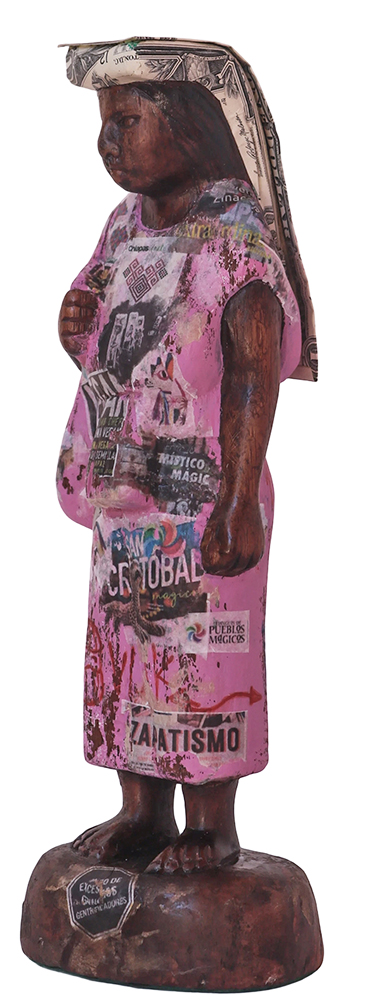

Segregated bodies | Darwin Cruz

Found object intervened: acrilic, dollar bill, wood

29 x 10 x 7 cm

2026

This is a woman from San Juan Chamula.The aesthetic I’m referencing here alludes to thegraffiti found on the streets of San Cristóbal de Las Casas. At times they may appear merely decorative, when in fact they are traces of protest against the exploitation of natural resources, gentrification, and other issues. With the commodification of culture, graffiti—and even Indigenous women themselves—become objects of observation for tourists on their tours. In my art, this now invites a critical gaze at this aspect of life in contemporary Indigenous communities.

Mutante capitaloceno | Darwin Cruz

Found object intervened: aluminum can

17 x 44 x 20 cm

2026

This work represents an armored reptile in honor of the animals that inhabit the banks of the Grijalva River. Water extraction by breweries reduces the habitat of native species and then contaminates it with their waste. This is where this crocodile is born—among cans, plastics, and debris. I model its scales (re)using fragments of aluminum taken from beer containers.

Lacerated trace | Darwin Cruz

Found object intervened: acrilic, oil paint, wood

33 x 51 x 17.5 cm

2026

The lifestyle of Indigenous peoples has become a tourist attraction and is positioned within the collective imagination in a romanticized way. But what about the harsh reality, with problems such as drug trafficking, addiction, and more? As a counter-representation, I made this figure of a Lacandon-Maya on a fragment of glowing wood, which stands in contrasts with the images promoted by the state.

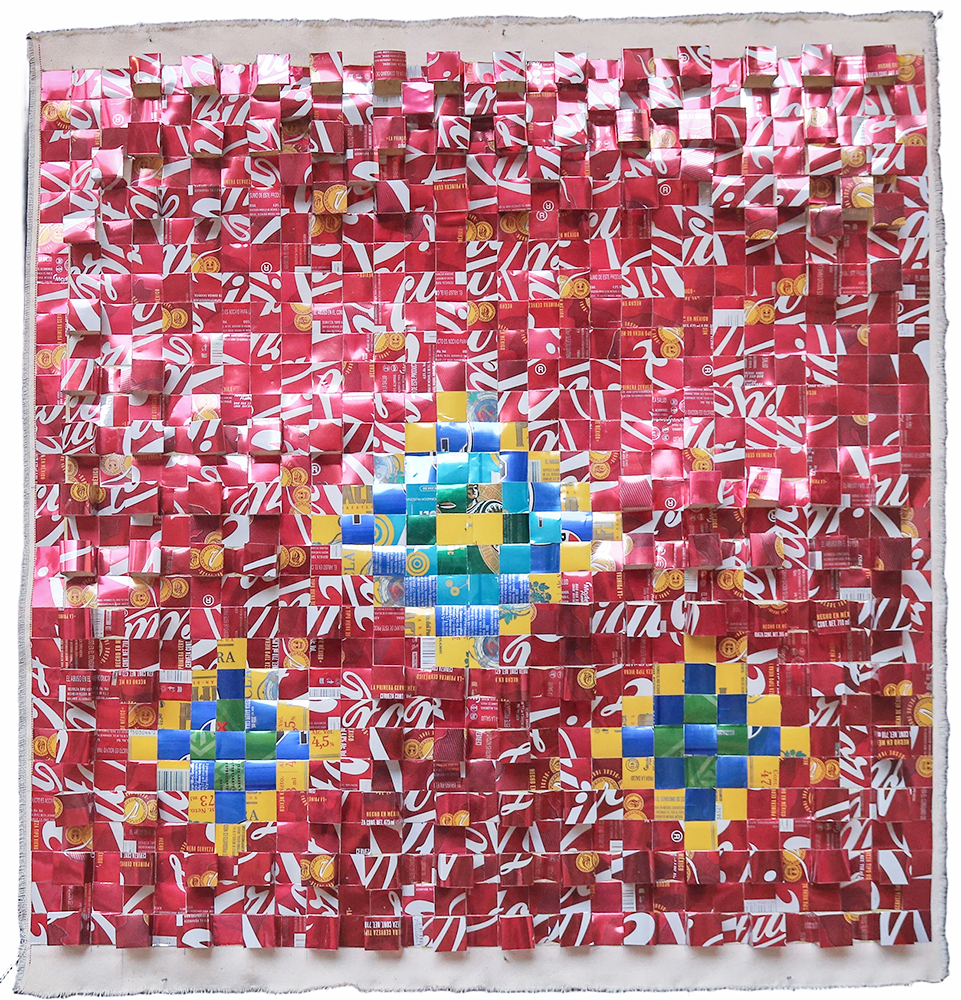

Warp of intoxications | Darwin Cruz

Aluminum and fabric

100 x 65 cm

2026

This work represents a fragment of a huipil, made from fragments of cans of commercial beverages, made of water of course. In the Highlands of Chiapas, water has become a privileged, even scarce, commodity, largely due to its exploitation by corporations, especially the soft drink and beer industries.

The consumption of industrialized products reaching the communities, is affecting our very symbolic, historical, and aesthetic values.

Sanctuary of the ancestors | Darwin Cruz

Wax, oil, and wood

15 x 18 x 9 cm

2023

Imagine a cave once inhabited by spiritual beings that gave meaning to the worldview of the Ch’ol peoples. The mountains and their caves are now being destroyed, turned into cement, or even into garbage dumps. Notice that the wood is charred, reflecting what is happening to our global environment.

Incandescent bones | Darwin Cruz

Acrylic, oil, charcoal on wood

44.5 x 35 x 4cm

2023

This piece portrays places in Ch’ol territory that still preserve the hearth as the core of daily life. Today, it has become more difficult to keep hearth fires fueled with firewood, and as a result gas stoves are gaining ground. The flavor of food cooked on a traditional hearth is incomparable!

Mi lum, mi otro lum y el lum-global | Gerardo K'ulej

terracotta comal

56 x 35 x 7 cm

2024

Lum, in Tsotsil, has many levels of meaning, from earth to territory to the spiritual center of the pueblo. My lum is not exactly my lum anymore; it is a fragmentation of my space which is both intimate and communal space, where the Maya is never simply Maya. We are “Tsotsiles” with new ways of creating and making milpa–life, where the hearth is displaced from the center of the home, where familiar dialogue around the fire is no longer possible—it is better with the ch’ojon tak’in (cell phone), communication at a distance, distant communication.

603,1988,2001 | Gerardo K'ulej

Intervened terracotta comal

70 x 23 x 3 cm

2024

Code that fragments the ideal of the Maya as a fixed concept, identity, or static culture. The cemet[clay griddle] as a circular (spiraling) artifact that turns through time, through memory, yet within the same territory, though across different eras and contexts. We are Maya from cities of towers, not of pyramids.

Estela Oxtoz | Gerardo K'ulej

Terracotta comal, stone, tecomate

33 x 48 x 20 cm

2025

This is a composition of forgotten elements once ubiquitous in the house, now displaced by industrialization. The comal, metate, and tecomate [for gridning corn, cooking tortillas y storing tortillas, keeping them warm.gourd, griddle and grinding stone] – here stacked elements, childhood memories that resist time and wear.

Today, the tortilla, as a global gastronomic element, has lost its local context—its symbolism and identity—is being reduced to mere consumerism.

.com1,0,0,0,0,1 | Gerardo K'ulej

Stone, tortilla, terracotta comal, QR code

30 x 50 x 35 cm

2025

Tri-, three, three hearthstones, no more.

Theoximyoket [traditional hearth of three stones, linked cosmically to the constellation others call Orion’s Belt)

Is like our bellybutton, ombligo, dislocated, discolocado.

Alienation.

The tortilla, a world, singluar, global,

Capital

Tortilla machines, whirring faster and faster.

Pukujil-00000 | Gerardo K'ulej

Wood, stone, corn cob, corn dough

50 x 35 x 14 cm

2025

Pukujil es like evilness which is hidden. Where is memory?

My pukujil has been transformed into a tool to strengthen my memory. The alloy of corn dough, wood, and stone is a technology that leads me back to my people

P'ilix bite (Grasshopper) | Gerardo K'ulej

Corn husks, corn cob, repeater, and corn

65 x 35 x 38 cm

2025

(In rural communities, internet companies are arriving, and one of them is called Bait, o “bite.” Hence the wordplay between bit and the pests that destroy the milpa.) Starting from this cyborg–grasshopper–shaped sculpture, I engage in a dialogue about the identity disruptions that technological devices have caused in Indigenous communities.